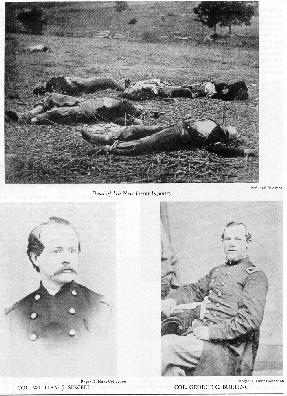

Working as quickly as possible, the photographic crew first captured the stark reality of Confederate dead gathered and laid out in rows for burial and, next, the startling contrast of a small group of dead Union soldiers lying scattered in a field. The Northerners were untouched and ignored, except by those (presumably Confederates) who had relieved the dead of their shoes, their equipment, and the contents of their pockets.

Gardner's major publication market was in the North, and the potential impact of these stirring and pitiful scenes was not lost on him. Several photographs were taken at each site from two opposing angles. With the experienced eye of an entrepreneur, the camera positions and angles were varied, resulting in two distinctly different views of the same subject. This technique would allow the views to be marketed later as two different groups of casualties.

The Gardner crew continued work at Gettysburg until July 7, taking an estimated 60 photographs, many of them dramatic, close-up, single subject shots. This method pro- duced highly salable views but left few clues as to precise locations on the battlefield. This mystery would remain unsolved for more than 100 years.

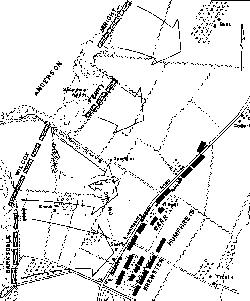

In 1975, William A. Frassanito published his grund-breaking work, Gettysburg: A Journey in Time. The exact locations of nearly all of Gardner's scenes were pinpointed here for the first time. By careful detective work, using landmarks sometimes as small as a single boulder, Frassanito proved that Gardner and company had probably worked exclusively on the southern end of the battlefield with respect to photographing bodies.

This was the area where the Union III and V Corps, along with elements of the 11 Corps, were devastated by the overwhelming Confederate attack on July 2. It is an area of landmarks, including numerous well-known farm buildings and many rock outcroppings and ridge lines. Here, too, were four of the battlefield's most prominent features-the low, rock- strewn hill called Little Round Top; the cluster of huge boulders known as Devil's Den, and the Peach Orchard and Wheatfield. All are easily recognized by even casual students of the battle.

One very important pair of photographs defied Frassanito's repeated attempts at identification. Almost as if by design, the views of the Union casualties contained absolutely no outstanding permanent terrain features. Despite initial success in proving that the two views of Union dead were in fact taken in the same place, the location of this historically significant scene remained unknown. These plates are identified as VI-13a and 13b, and VI-14 in Frassanito's book.

However, uniforms may also be considered as a sort of "landmark." The soldiers in the photographs, whoever they might be, were all wearing the U.S. Army issue dress frock coat. Although not uncommon earlier in the war, by 1863 this garment was rapidly being replaced for campaign wear by the much more practical four-button fatigue blouse. Perhaps this was part of the key to identification of the regiment to which these men belonged and thereby to the location itself.

Armed with the knowledge of several regiments

believed to have been wearing frock coats,  numerous

trips were made to Gettysburg in 1975 and 1976 to examine the terrain where

these frock-coated regiments fought. It was obvious that there was only

one spot, a few square feet on the battlefield, where both views taken

by Gardner would line up. Finding this place would take more than guess

work.

numerous

trips were made to Gettysburg in 1975 and 1976 to examine the terrain where

these frock-coated regiments fought. It was obvious that there was only

one spot, a few square feet on the battlefield, where both views taken

by Gardner would line up. Finding this place would take more than guess

work.

In 1986 work began with fellow historian Les Jensen and artist Don Troiani on a longtime dream-a book intended to document as completely as possible the battle dress, arms, and equipment of the armies of Gettysburg. Along with everything else, this research would determine exactly which of the 249 Union infantry regiments engaged wore the frock coat during the battle. Although ten years had passed since the first serious attempt at identifying the Union dead in the photographs, the subject was still very much in mind. The conviction had never been abandoned that the uniform coat worn by the corpses was one key to their identification, and it was determined to follow up ever), new lead with a search of the appropriate battlefield area.

A little more than a year into this project, on a cold, day on the southern end of the Gettysburg Battlefield all the work was finally rewarded. On that day, at a spot which even today seems oddly remote, I realized I was the first person in 125 years to know the identity of the Union dead photographed by Alexander Gardner on July 5, 1863. These soldiers, so long unknown, had been members of Col. William J. Sewell's 5th New Jersey Infantry. They had fought and died on the advanced line occupied and held by the regiment for a few dramatic minutes on the afternoon of July 2, 1863.

Those who have attempted to document uniforms for even one Civil War regiment will confirm that the process involves plowing through numerous original records. Many of these documents can be found scattered throughout the mountain of Civil War requisitions, inspection reports, and orders stored in the National Archives. Here was found a combined equipment requisition and deficiency report for Col. George C. Burling's 3rd Brigade, Second Division, III Corps, which consisted of six volunteer infantry regiments: the 5th, 6th, 7th, and 8th New Jersey; the 115th Pennsylvania; and the 2nd New Hampshire.1

The possible significance of this document

was immediately evident. By now research had shown that almost no Union

regiments carried both coat and blouse into the campaign. This report,

written in the field on two hand-drawn forms and filed two weeks after

the battle, made no provision for either reporting or requesting fatigue

blouses, only frock coats. Equally exciting was the fact that this brigade,

as part of the III Corps, had definitely been engaged in the area known to have been photographed

by Gardner. Still, this per se was not proof that other Federal regiments

were not wearing frock coats at Gettysburg, only that these particular

regiments were.

III Corps, had definitely been engaged in the area known to have been photographed

by Gardner. Still, this per se was not proof that other Federal regiments

were not wearing frock coats at Gettysburg, only that these particular

regiments were.

As soon as possible, another trip to Gettysburg was made - this time to look at the various areas occupied by Burling's six regiments. Burling's brigade was unique in that during the frantic fighting of the afternoon of July 2, it had not fought as a unified command. Instead, each regiment- had been thrown into the battle at different locations in an attempt to bolster the hard-pressed III Corps line.

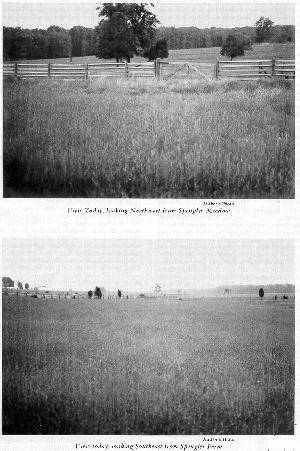

Referring to the 1863 photographs, the area concerned is an open field devoid of any of the outcroppings of rocks so common to the Gettysburg area, and with fences and trees, long since gone from the scene. This lack of permanent background which had originally prevented the determination of the location of the photograph now worked, curiously, to assist it. Only two regiments in the brigade the 5th and the 7th New Jersey-fought and suffered casualties in such a featureless place.

First explored was the ground where the 7th New Jersey fought, a field just east of the Emmitsburg Road. Nothing seemed to match, but the 7th was not totally eliminated as a possibility.

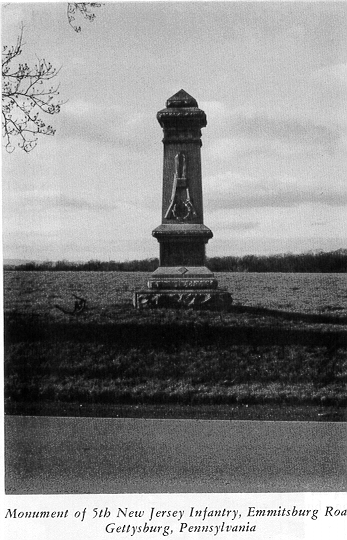

On another day the area was examined in front of the 5th New jersey's monument: the fields north of the Sherfy house and just west of the Emmitsburg Road. Again, nothing matched, at least not in the two directions necessary to align with the visible terrain in the original photographs. Walking back to my car, I stopped to read the 5th New jersey's monument. It was cold and nearly dark, but despite this, what I saw nearly sent me back onto the field. On the left side was the inscription: "The regiment first held the skirmish line 400 yds to the Front and left of this spot, and afterwards took position in the line of battle here."

For an instant, it felt as if the veterans of the 5th were talking to me. I resisted the urge to stumble over the fields in the twilight and instead, drove home and laid out several maps bearing on the area. The 400 yards left front (mentioned on the monument) would put the 5th New Jersey Infantry south of the H. Spangler house-in a wide open field.

On the next trip, for no specific reason, I decided to walk into the same area from the opposite direction. It was almost too easy. The original photographs were etched in memory by now. Approaching the area south of the Spangler barn, I could see where the close-up view was taken. I stopped to savor the moment, then walked ahead, stopped again, and turned. There behind me was the second view. The terrain had changed surprisingly little in 125 years. This, combined with the misty, gray, late winter day added to the feeling that I had somehow stepped back in time into those colorless 1863 photographs.

In the following weeks I returned to the spot several times to take comparative photographs. By now it was not enough simply knowing the who and where; I needed to know why. Why had the 5th New Jersey taken this isolated position so far in front of the main Union battle line? Why was this seemingly insignificant patch of ground worth dying for? Further research in both official reports and individual service records held the answers.

To a certain point, the Gettysburg history of Burling's brigade (including the 5th New Jersey) is the same as the rest of the Union Army's. They had shared defeat at the battle of Chancellorsville, just west of Fredericksburg, Virginia. Retreating back across the Rappahannock River, the next few weeks were spent keeping an eye on Robert E. Lee's Confederates and refitting for the campaign and battles sure to follow. Finally, in mid-June the Rebels broke loose and- headed north. Lee had taken the initiative and decided to move the war to his enemy's home ground.

Burling's regiments also shared in the long, exhausting marches needed to keep a strong force of Union soldiers between the Confederates and Washington, D.C. Most of the Union Army, including Burling's men, were in Maryland on July 1 when the first elements of both armies finally clashed just west of Gettysburg.

The brigade remained guarding the roads near Emmitsburg until dawn of the next day. It was evident now that the fighting of July I was the beginning of a major battle, and every man was needed. Propelled by the head)combination of excitement and fear, Burling's men reached the area occupied by the 11 Corps between 9 and 10 a.m. the extreme left of the Union line, near Little Round Top and Devil's Den. In the best army tradition of hurry up and wait, the brigade ",as placed in reserve and waited. In the afternoon, the corps commander, Maj. Gen. Daniel E. Sickles, made the fateful, and to this day controversial, decision to move his corps forward to occupy the high ground on the Emmitsburg Road. Retaining possession of Devil's Den, he stretched his line west to the road, then with his center in the Peach Orchard, north along the road itself.

Burling's brigade, still in reserve, moved forward to a wooded area several hundred yards behind the line. Rested now from the morning's march, the men took advantage of the shade and continued to wait.2

About 4:30 p.m., all hell broke loose on the left of Sickles' III Corps. A furious attack by determined Confederates, including the famous Texas Brigade, slammed into the Union line. Fighting spread along the III Corps line as other Rebel brigades joined the assault. As the intensity of the fighting increased, cracks began to appear in the hard-pressed III Corps line. In response to urgent calls for reinforcements, Burling's two strongest regiments, the 2nd New Hampshire and 7th New Jersey, were hurled into the fight. The 5th New Jersey was next. A forward screen was needed to protect Lt. F. W. Seeley's Company K, 4th U.S. Artillery, which had gone into position with other elements of the III Corps on the Emmitsburg Road. This sector of the line was not yet under attack, but it was only a matter of time. Responding to orders, the 5th New Jersey rushed forward, crossed the road, and headed down a long slope. Sewell fanned his command left and right into a single thin line about loo yards ahead of the rest of the corps.3

The 5th New Jersey was hardly in position before the air above them came alive with bursting artillery shells. A Confederate battery had opened fire on the main III Corps line. Company K was a prime target: the Jersey men were in the direct line of fire.

Under a rain of shrapnel, men began to fall. For a half hour that must have seemed like forever, the regiment maintained position as its casualty list grew. Suddenly, the woods 200 yards to the front showed signs of activity. A scattering of troops began to emerge. But their green uniforms identified them as members of the 1st United States Sharpshooters-snipers-sent far forward to slow the Confederate infantry attack that was sure to come. And come it did. Berdan's Sharpshooters had barely reached the Union line when the wooded ridge was filled by a Confederate battle line-five Alabama regiments-a full brigade, under the command of Brig. Gen. Cadmus M. Wilcox.

Only minutes before, a thunderous assault by another Rebel brigade had set the ridge line and Peach Orchard

Isolated now with "friendly" fire at their rear and enemy fire in front, Colonel Sewell tried to rally his small command on the right of his line. Expecting reinforcements and feeling responsible for the safety of Company K, he was determined to hold this position.4 Men were falling - not from artillery now-but from rifle-muskets in the hands of the oncoming Confederates.

Within minutes, Lt. Thomas Kelly went down, shot in the chest. Pvt. Edward Martin fell; he would never see his son born just a week before. Samuel Henselman was shot dead, as were 18-year-old Cpl. Edgar Van Winkle and 45-year-old Heinrich Troch. Others were being hit all around them; still, there was no sign of help. 5

Now Sewell's choices were clear: surrender, die, or retreat. Maintaining as much order as possible, the remnants of the 5th New Jersey scrambled toward the protection of the III Corps line on the Emmitsburg Road. Rebel bullets continued to rip into them.

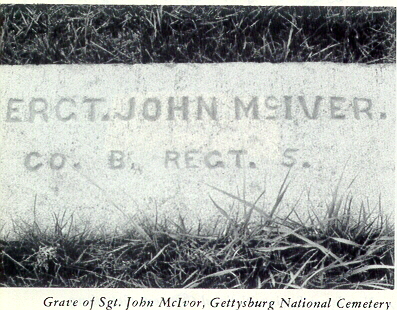

Thomas Hannagan staggered and fell as a minis ball smashed into his right leg. Sgt. John Chase went down with a bullet in the left thigh. As Levi Hall and Louis Law of his company tried to help him, Hall was shot as well. As the group neared the road, John McIver was shot in the back, but somehow managed to struggle on.

They found no sanctuary as they reached the road; the fire was merciless. Colonel Sewell was able to reform the regiment, probably near where its monument stands today. Sewell himself was wounded as the full force of the Confederate attack crushed the III Corps line. With both other senior officers also down, the command fell to 30-year-old Capt. Thomas Godfrey of Co. F, in gentler times an artist in Philadelphia. Along with the badly scattered III Corps, what remained of the regiment was forced back to the main Union line. 6 In the confusion an turmoil, Seeley's Company K also made it back, under the protection of an, other regiment.

It was hardly more than an hour since the 5th New Jersey had moved forward to the skirmish line. For that time, detached from the main army if only by 100 yards, they had written their own history. Of the 190 who had marched from Emmitsburg on the morning of July 2, only half answered roll call on the morning of July 3. Among the casualties were 14 who lay dead in the field south of the Spangler buildings.

The tumultuous events of July 3, including the Confederate assault known as Pickett's Charge, required no further sacrifice from the 5th New Jersey. Pickett's and Pettigrew's repulse doomed the Southern invasion. By the evening of July 4, the Confederate Army had begun its retreat to Virginia.

Sometime on July 4, Colonel Burling ordered a small detachment from each of his regiments to go forward to the area of the July 2 fighting. Although the stated purpose was to collect arms and equipment, it is certain that the fate of comrades abandoned by necessity on the 2nd was foremost in the minds of those who went.7

One who went onto the fields, probably with the detail from the 5th New Jersey, was Pvt. Isaac Kelly of the 1st New Jersey. He found the mangled body of his brother, Thomas, and that evening wrote a pain-filled letter home to their parents.

July 4th 1863On the afternoon of July 5, a burial party moved down the slope frm the Emmitsburg Road to tend to a scattered group of 14 dead Union soldiers, wearing the dress frock coat of the U.S. Infantry. Probably with some curiosity, they waited a short while and watched as a photographer and his crew took several photographs of the grisly scene. Then they buried the bodies in shallow, temporary graves.

On the Battle Field

Near Gettysburg Pa.My Dear Parents,

It is with great sorrow that I write you these few lines, but I cant refrain from it, I must let you know it. it is the death of my Dear Brother Thomas. he was wounded on Thursday in the Breast. while leading his Company to Victory, his regiment was flanked and had to fall back. Therefore he was left on the Battle field. Mortelly wounded, yesterday during the Battle he had his both legs shot off and I suppose he deid wright away after he had his legs shot off. all his Company's are very sorry about him. he had nothing left in his Pocket except a little flag, which I send you. please safe it as a Memento for the family. I just seen him. he will be Burried in the Morning, his Company will try to send him home after the Battle is over. I am very well and hope this will find you all well. I can not write any more for my Breast is bursting with Sorrow. write soon

Your affectionate son

Isaac Kelly

Co H, 1st Regt. NJV

To his Father and family

P.S. This is the flag he had in his Pockets he was

Robed of every things else.Your son,

I. Kelly"

The New Jersey section of the National Cemetery contains 78 graves. Only six are identified as 5th New Jersey men. Of these, four died in field hospitals; their identities could be easily learned. One of these four was Sgt. John McIver, who had been wounded during the retreat. On July 8, he wrote home from the field hospital of the III Corps to tell his young wife that he was "amongst the wounded. . .." He died on July 16."

There are 24 unknowns buried in the New Jersey section. It seems most likely some of these are 5th New Jersey men.

In the final assessment, it can simply be said that at Gettysburg, the regiment did its duty. They held the position assigned them as long as humanly possible and under the trusted and steady leadership of Colonel Sewell, retreated in good order.

It seems strange that no one from the 5th New Jersey ever stepped forward to identify the Gardner photographs. Perhaps those who knew never saw Gardner's publications. Or maybe the confusion of that terrible hour blotted the details of the scene from their memories. It could be, too, that they simply knew, as perhaps did Alexander Gardner, that identification should be left to one whose generation had no intimate relationship with those involved.

Over the years, the Gardner photographs have come to symbolize all the Union dead at Gettysburg. Because of their gallant conduct and bravery, it is certainly fitting that fate chose the men of the 5th New Jersey for this role. It is even more fitting that these men, all volunteers, should remain as a symbol of the dutiful sacrifice of an Army composed almost entirely of "citizen" soldiers.

As for me, I feel privileged to have played a small part in honoring these deserving soldiers, no longer unknown. To walk for a short time in the shadow of such men as Sewell, Kelly, and McIver is one of the special rewards given to those who work as historians.

2. Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Series 1, Vol. xxvii, Pt. 1, p. 575.

5. National Archives, Record Group 15, Records of the Veteran's Administration, pension files of Kelly, Martin, Henselman, VanWinkle, and Troch.

6. Record Group 15, pension file of Thomas Godfrey.

7. Record Group 393, Entry 68, Records of the 1st-4th Division, 11 Corps, incl. III Corps records.

8. Record Group 15, pension file of Thomas Kelly.

9. Record Group 15, pension file of John McIver.

10. Record Group 15, pension files.