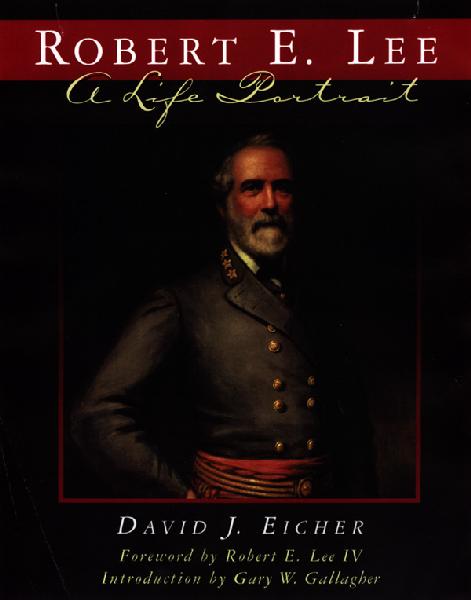

Available at bookstores or call (800) 275-8188, see www.globaldialog.com/~eicher/index.htm

I am truly glad that Dave Eicher's book, which brings together all of the important images of the General and offers a valuable glimpse of Lee the man and Lee the commander, has arrived to help celebrate my great-grandfather's life." - from the foreword by Robert E. Lee iv, General Lee's great-grandson.

Whatever readers think about Robert E. Lee, they should be grateful that Dave Eicher put together this book. A turn through its pages underscores how photographs and artworks have assisted the printed word in shaping the ways in which Americans interpret Robert E. Lee. - from the introduction by Gary W. Gallagher, author and editor of Lee the Soldier and numerous other works.

"With an increasing admiration of your constancy and devotion to your country, and a grateful remembrance of your kind and generous considerations for myself, I bid you an affectionate farewell." With those words, delivered after the surrender at Appomattox Court House, Robert Edward Lee ended his legendary military career. Despite his ultimate military defeat and the fact that his surrender signaled the end of the Confederacy itself Lee is remembered as perhaps the most celebrated and revered of all American generals.

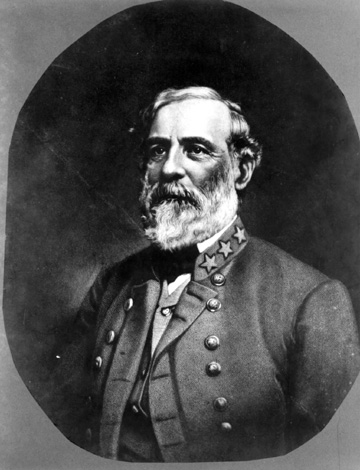

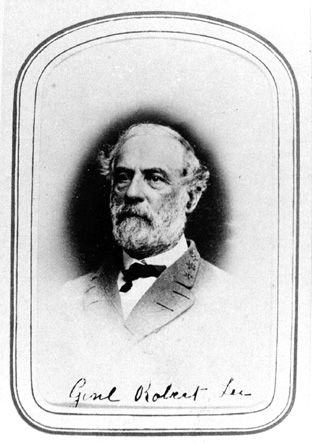

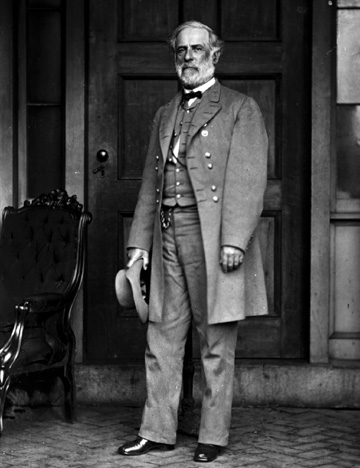

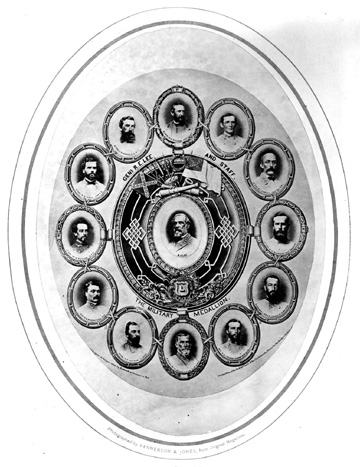

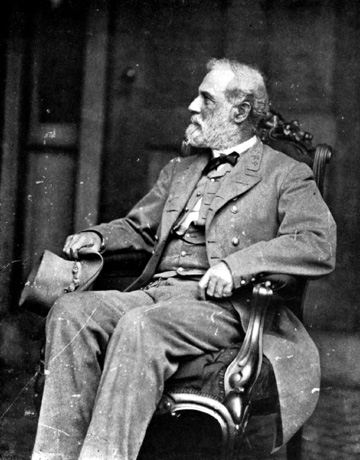

Eicher's portrait of Robert E. Lee presents a life story superficially familiar to readers of American history yet containing myriad complexities that will entertain even seasoned Civil War buffs. He draws on a multitude of letters of Lee himself, family members, and fellow army officers. Throughout the story, Eicher presents the most comprehensive collection of images relating to Lee's life ever assembled, some 375 in all, 28 reproduced in color, drawn from each of the most significant repositories of Lee images. Not only are all 71 Lee photographs from life presented, but also many photographs of family members, friends, subordinate commanders, relics, and significant places associated with the Lee story. In addition, the work offers reproductions of the most significant portraiture and engravings involved with the Lee story. Some of the photographs of Lee himself are previously unpublished.

This unparalleled collection of Lee imagery complements a text that analyzes Lee the man, his privileged ancestral background, education at West Point, engineering duties in the army, and Mexican War experiences. The narrative explores Lee's family life, management of the U.S. Military Academy, and his attitudes toward the convoluted issues that erupted as the Civil War approached. Detailed coverage of Lee's activities in the Confederate war effort gives way to a synopsis of his postwar educational activities and the transformation of man into legend after his death, chiefly by Southerners who continued to fight the war on paper.

Eicher demonstrates that Lee, despite a limited relationship with his disgraced father and a tenuous position in a large, aristocratic Virginia society, rose above psychological handicaps and prospered. That he was an old-style aristocratic thinker, however, disabled him from fully appreciating the revolution going on around him. Surprises will surface in Eicher's book even for seasoned Lee fans, such as the discoveries that Lee may count as relatives Jefferson Davis, Stonewall Jackson, Jeb Stuart, and eleven U.S. presidents including - of all people - Ulysses S. Grant.

This work is certain to become a treasure among readers of Civil War history, the American past, and biographies of notable world figures.

Dave Eicher is managing editor of Astronomy magazine. His long-standing interest in Civil War history has led him to produce Civil War Battlefields: A Touring Guide, The Civil War in Books: An Analytical Bibliography, and the annual Civil War Journeys calendar. He lives with his wife and son in Waukesha, Wisconsin.

Back near Fredericksburg, on 18 January, the Federal army under Burnside began to move. Lee was apprehensive and began two days of intense scouting, after which the Yankees reformed and deactivated. Burnside had found the roads hopelessly mired, and the expedition came to be called the Mud march."Lee then began to fortify the whole Rappahannock line, a process that continued for several weeks. Although Confederate fortunes were strong, Lee warned Richmond that the coming months would perhaps decide the war. "The enemy will make every effort to crush us between now and June," he wrote," and it will require all our strength to resist him."1

The Yankees were not exactly doing their best. Lincoln replaced the incompetent Burnside with the hotheaded and intemperate Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker. "General Hooker is obliged to do something," Lee wrote Agnes on 6 February." I do not know what it will be. He is playing the Chinese game, trying what frightening will do. He runs out his guns, starts his wagons and troops up and down the river, and creates an excitement generally. Our men look on in wonder, give a cheer, and all again subsides in statu quo ante bellum."2

It was clear that Hooker planned no action until springtime weather arrived. Meanwhile, shortages began to significantly affect the Army of Northern Virginia. Food shortages posed the biggest problem, for horses as well as the soldiers, and shortages of horses and artillery supplies were becoming serious. Moreover, the condition of the railroads in Virginia had deteriorated rapidly." General Lee writes anxious letters to which he endorses that he has long foretold the scarcity [of food], that transportation is the present difficulty," wrote Robert G. H. Kean, chief of the Bureau of War, on 1 April. "The railroads are worn out. . . . General Lee has fought all winter against this, and now the evil, which much might have been done to remedy during the winter months, is nearly irremediable, and the campaign about to begin."3

During the first week of April Lee caught a bad cold, which was worsened by the environment inside his tent. Doctors moved him to the nearby Yerby House, thinking he had developed pericarditis. He experienced occasional sharp chest pains, sustained a fever, and felt sore in his back and arms. By 11 April he was able to ride Traveller again, although his legs were weak and his pulse was about 90 per minute. The next day a worrisome cough seemed to improve.4 "The doctors were tapping me all over like an old steam boiler before condemning it," he wrote.5

Throughout this month the armies had been maneuvering on opposite sides of the Rappahannock. But the army could discern no clear Federal movement. During these last calm days before the storm, on 27 April, Stonewall Jackson's wife Mary Anna attended a prayer meeting at her husband's headquarters. There she met Lee for the first time. " I remember how reverent and impressive was General Lee's bearing, and how splendid he looked, with his splendid figure and faultless military attire," she wrote." General Lee was always charming in the society of ladies, and often indulged in a playful way of teasing them that was quite amusing. He claimed the privilege of kissing all the pretty young girls, which was regarded by them as a special honor."6 And then came the storm. On the morning of 29 April, a distant rumble marked the initiation of Hooker's crossing of the Rappahannock. The campaign of Chancellorsville had begun.

At this time, Lee sought to protect the Virginia Central Railroad, maintain his communications with the Shenandoah Valley, and gather supplies from the area north of Richmond. To prevent a siege of the capital, he determined to hold his line of defense along the Rappahannock and not to allow Hooker to turn his left flank. Instead of falling back, he made a risky attempt to turn Hooker's turning movement.7

Hooker's plan to turn Lee's left developed into a sound one: Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick placed the 1st and 6th corps opposite Fredericksburg and crossed below the city. Maj. Gen. Darius N. Couch and the bulk of the 2d corps crossed at U.S. Ford opposite Chancellorsville, and Maj. Gens. George G. Meade (5th corps), Henry W. Slocum (12th corps), and Oliver O. Howard (11th corps), crossed at Germanna Ford and Ely's Ford and marched on Chancellorsville from the north and west.

On 1 May the battle of Chancellorsville, named for a brick Tavern House at a crossroads, began in earnest. The area was a difficult one for tactical maneuvers: dubbed the Wilderness, the surrounding dense woods contained thick second-growth oak and pine with brushy undergrowth. At first the fighting was indecisive, with attacks and counterattacks washing back and forth before Union Maj. Gens. Slocum and Winfield Scott Hancock stubbornly held their ground. Hooker then utterly lost his nerve and ordered a withdrawal, which he later countermanded, but it was too late to reassemble the advanced positions. Lee cautiously followed and worried about Sedgwick's possible drive from the east.

Now Lee's characteristic boldness and desire to grasp the offensive took over and he hatched a controversial and spectacularly successful plan. Jackson would take half of the army at hand, some 26,000, and march around the Union right flank, attacking it in force from the west. Early in the morning of 2 May, Lee and Stonewall Jackson had a fateful conference to discuss tactics. "Some time after midnight I was awakened by the chill of the early morning hours, and, turning over, caught a glimpse of a little flame on the slope above me," wrote James Power Smith, a staff officer of Jackson's. "Sitting up to see what it meant, I saw, bending over a scant fire of twigs, two men seated on old cracker boxes and warming their hands over the little fire. I had but to rub my eyes and collect my wits to recognize the figures of Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson."8

Hooker strengthened his line at Hazel Grove and by early afternoon Jackson had reformed for attack after the early morning march. "The enemy has made a stand at Chancellor's, which is about two miles from Chancellorsville," Jackson wrote Lee at 3 p.m." I hope, as soon as practicable, to attack. I trust that an ever-kind providence will bless us with success."9

Jackson completed his amazing flank march to the west of the Union army and struck at 6 p.m., pushing back the Yankees initially before they regrouped and uncoordinated actions by Jackson's subordinates decelerated the action. About darkness Jackson set off to reconnoiter a route to entrap Hooker, but returning, he was accidentally shot by his own troops, hit in his left humerus and right hand. His left arm was amputated at an aid station on the Orange Turnpike and Stonewall was put into an ambulance that would take him toward Richmond. At 12 midnight I started for General Lee's . . . to inform him of the state of our affairs, making a wide detour, as the enemy had penetrated our lines,"wrote Jedediah Hotchkiss, Jackson's topographer. He was much distressed [about Jackson] and said he would rather a thousand times it had been himself. He did not wish to converse about it.”10 Finally, Lee told Hotchkiss, I know all about it and do not wish to hear any more it is too painful a subject."11

The next day Lee wrote his fabled lieutenant. I have just received your note informing me that you were wounded,"he wrote. I cannot express my regret at the occurrence. Could I have directed events, I should have chosen for the good of the country to have been disabled in your stead."12

On this morning of 3 May the battle of Chancellorsville raged on without Jackson. The Federal battle line now had a bulge extending to the south around Chancellorsville Tavern and Fairview, another house site, after Hooker withdrew from Hazel Grove. This bulge consisted of the forces of Maj. Gens. Couch, Slocum, and Daniel E. Sickles. Meanwhile, Maj. Gen. James E. B. Stuart assumed temporary command of Jackson's corps to the west, and the divisions of Maj. Gens. Dick Anderson and Lafayette McLaws to the east, with Maj. Gen. Jubal A. Early opposing Sedgwick at Fredericksburg. As the Confederate assaults achieved some initial success, the Federal commander Hooker leaned on a column of the Tavern. Just then a shell hit the column, knocking Hooker senseless. About this time General Lee rode up with some of his staff from the direction of Salem Church followed by Confederate infantry," wrote the artillerist William T. Poague. Cheering broke out and was taken up by the various bodies of Confederate troops as they converged at this central point."13 By midmorning Hooker ordered a withdrawal, just as Sedgwick was having success pushing westward from Fredericksburg.

By late afternoon Sedgwick battled his way across the Fredericksburg battlefield of the previous December to Salem Church, Early retreating southward; Sedgwick faced McLaws instead. About this time a courier rode up to Lee and staff with the news about Sedgwick. When his eye fell upon General Lee he made directly for him, and I followed as fast as I could," wrote Robert Stiles. He dashed to the very feet of the commanding general, indeed almost upon him, and gasping for breath, his eyes starting from their sockets, began to tell of dire disaster at Fredericksburg — Sedgwick had smashed Early and was rapidly coming in on our rear. I have never seen anything more majestically calm than General Lee was . . . something like a grave, sweet smile began to express itself on the General's face, but he checked it, and raising his left hand gently, as if to protect himself, he interrupted the excited speaker, checking and controlling him instantly, at the same time saying very quietly: "I thank you very much, but both you and your horse are fatigued and overheated. Take him to that shady tree yonder and you and he blow and rest a little. I'm talking to General McLaws just now. I'll call you as soon as we are through."14

Darkness brought the struggle to a close. On 4 May the Army of Northern Virginia concentrated against Sedgwick but the attack that came in early evening was a piecemeal affair. Following more maneuvering, Lee planned a decisive attack against Hooker for 6 May, but Hooker initiated an early morning retreat. The battle, hailed by many as Lee's masterpiece, was over. The general commanding had the honor to communicate news of the battle to President Davis, which he did as follows: Yesterday General Jackson, with three of his divisions, penetrated to the rear of the enemy, and drove him from all of his positions from the Wilderness to within 1 mile of Chancellorsville. He was engaged at the same time in front by two of Longstreet's divisions. This morning the battle was renewed. He was dislodged from all his positions around Chancellorsville and driven back toward the Rappahannock, over which he is retreating. Many prisoners were taken, and the enemy's loss in killed and wounded large. We have again to thank Almighty God for a great victory. I regret to state that General Paxton was killed, General Jackson [wounded] severely, and Generals Heth and A. P. Hill slightly, wounded."15

The victory at Chancellorsville dramatically accelerated the confidence of the Army of Northern Virginia and of the Confederate cause, despite the shortages. "The past week has been a most eventful one,"Walter Taylor wrote on 8 May. The operations of this army under Genl Lee during that time will compare favorably with the most brilliant engagements ever recorded."16 Yet there was a heavy price to pay for Chancellorsville. Among the army's 13,000 casualties during the campaign would be its greatest hero of the moment, Jackson. Taken by ambulance to Guinea's Station, he contracted pneumonia and declined rapidly on 10 May. On Jackson's deathbed, surgeon Hunter Holmes McGuire recorded the last, wandering, delirious spoken passages of Jackson. Shortly before he died, Jackson called out for A. P. Hill, ordering him to" prepare for action," and continued, "Pass the infantry to the front rapidly! Tell Major Hawks . . . let us cross over the river, and rest under the shade of the trees."17 On the same day Lee wrote James A. Seddon, the Secretary of War. "It becomes my melancholy duty to announce to you the death of General Jackson," he wrote. "He expired at 3.15 p.m. to-day. His body will be conveyed to Richmond in the train tomorrow, under the care of Major Pendleton, assistant adjutant-general. Please direct an escort of honor to meet at the depot, and that suitable arrangements be made for its disposition."18 To Mary, he wrote on 11 May, "In addition to the deaths of officers and friends consequent upon the late battles, you will see that we have to mourn the loss of the great and good Jackson. Any victory would be dear at such a price. . . . I know not how to replace him. God's will be done!"19

Following Chancellorsville, the eastern armies flowed back into their old defensive positions along the Rappahannock. By now troubling signs began to emerge. The Army of the Potomac was as formidable as ever. Out west, Grant was threatening Vicksburg, capture of which would cut the Confederacy in half and return control of the Mississippi to the Union navy. In May Grant fought a series of battles from Jackson to Champion's Hill to Big Black River before laying siege to the entrapped Pemberton. In Richmond, something needed to be done. Longstreet proposed shifting troops to strike the centrally placed Rosecrans in Tennessee, drawing Grant away from Vicksburg. But Lee refused to look at the war in that broad a context and stuck to his self-appointed priority of focusing on Virginia. "The Secretary of War dispatched Gen. Lee a day or two ago, desiring that a portion of his army, Pickett's division, might be sent to Mississippi,"wrote the war clerk John B. Jones on 15 May. "Gen. Lee responds that it is a dangerous and doubtful expedient; it is a question between Virginia and Mississippi; he will send the division off without delay, if still deemed necessary. The President . . . says it is just such an answer as he expected from Lee, and he approves it. Virginia will not be abandoned."20

The situation was thus set for the Gettysburg campaign. Defending Virginia alone would not accomplish anything and would cast time as a Union advantage. So Lee concocted a plan to launch another raid into the North, as he had in the Maryland campaign the previous autumn, to draw the war away from Virginia, shift Union forces away from the West, perhaps win foreign recognition, and stay on the offensive. This would put time on his side. He reorganized the army and placed Richard S. Ewell in command of Jackson's old corps. On 9 June Stuart, now commanding the army's cavalry, held a grand review at Brandy Station. "A mimic battle had taken place, preceding the real one,"wrote John Esten Cooke of Stuart's staff. "The horse artillery, posted on a hill, fired blank cartridges as the cavalry charged the guns; the columns swept by a great pole, from which the white Confederate flag waved proudly in the wind. General Lee, with his grizzled beard and old gray riding cape, looked on, the centre of all eyes; bands played, the artillery roared, the charging squadrons shook the ground, and from the great crowd assembled to witness the imposing spectacle shone the variegated dresses and bright eyes of beautiful women, rejoicing in the heyday of the grand review."21

The next day a massive cavalry battle was fought at Brandy Station pitting Stuart's cavalry against the Federal horse soldiers of Maj. Gen. Alfred Pleasonton. About 10,000 men fought on each side, and the result was highly confused. Rooney was badly wounded in the leg and his father saw him borne off the field on a stretcher. Two days later he wrote Charlotte Wickham Lee, Rooney's wife. "I am so grieved, my dear daughter," he wrote, "to send Fitzhugh to you wounded. But I am so grateful that his wound is of a character to give us fully hope of a speedy recovery. . . . As some good is always mixed with the evil in this world, you will now have him with you for a time, and I shall look to you to cure him soon and send him back to me."22 The army was now in a full northward movement, heading for Pennsylvania, using the Blue Ridge mountains as a screen. Stuart, harassed by Pleasonton, protected the army's advance up to the Potomac River. Hooker cautiously pursued, with relatively good intelligence about the enemy's whereabouts, whereas Lee lacked such knowledge. "Yankeedom is in a great fright at the advance of Lee's army to the Potomac," wrote Robert G. H. Kean on 21 June, "and considers this part of Pennsylvania south of the Susquehanna as good as gone. . . . General Lee's plans are still wrapped in profound mystery, at least to us in Richmond except doubtless the President and Secretary."23

On the 23d the Army of Northern Virginia was mostly safe across the Potomac." I did not know until we commenced marching that Genl. Lee intended to send us back in the Union, but here we are all in the Union again,"wrote Clement A. Evans.24 Four days later the army had dispersed into positions as follows: Longstreet at Chambersburg, A. P. Hill at Greenwood, Early at York, and Ewell below Carlisle. Lee sent a dispatch to Ewell, "If Harrisburg comes within your means, capture it."25 Stuart, back in Virginia, received a dispatch from Lee providing orders, and the night was dripping rain, and Stuart was asleep. So Henry B. McClellan of Stuart's staff opened it, and the letter discussed at considerable length the plan of passing around the enemy's rear. It informed General Stuart that General Early would move upon York, Pa., and that he "was desired to place his cavalry as speedily as possible with that, the advance division of Lee's right wing."26 Upset at being caught off guard at Brandy Station, Stuart hatched a plan to ride northeast of the Federal army, now concentrated at Frederick, to capture supplies and restore his reputation. He captured a train of 125 wagons and headed north to link up with the army.

Late on 28 June a spy of Longstreet's, Edward Harrison, reached Chambersburg with alarming news. The Yankees were concentrated about Frederick and Hooker was out - Maj. Gen. George G. Meade was the new commander of the Army of the Potomac. "I was roused by a detail of the provost guard bring up a suspicious prisoner," wrote G. Moxley Sorrel of Longstreet's staff. " I knew him instantly; it was Harrison, the scout, filthy and ragged, showing some rough work and exposure. He had come to report to the General, who was sure to be with the army,' and truly his report was long and valuable. . . . [Harrison] described how they were even then marching in great numbers in the direction of Gettysburg, with intention apparently of concentrating there. . . . [Longstreet] was immediately on fire with such news and sent the scout by a staff officer to General Lee's camp near by. The General heard him with great composure and minuteness."27

Lee ordered a concentration at Cashtown, which offered a good defensive position and the ability to strike at a flank of the advancing Federal army. On 30 June the visiting British military observer Arthur J. L. Fremantle described the Confederate commander: "This morning, before marching from Chambersburg, General Longstreet introduced me to the Commander-in-chief [sic]. General Lee is, almost without exception, the handsomest man of his age I ever saw. He is fifty-six years old, tall, broad shouldered, very well made, well set up a thorough soldier in appearance. . . . He generally wears a well-worn long gray jacket, a high black felt hat, and blue trousers tucked into his Wellington boots. I never saw him carry arms, and the only mark of his military rank are the three stars on his collar."28 These stars are the ones erroneously identifying Lee as a Colonel, the peculiarity of his uniform mentioned previously.

Brig. Gen. John Buford's Federal cavalry had moved into Gettysburg, a town where 10 roads converged, and on the early morning of 1 July Confederates under Henry Heth, on a foraging mission, encountered Buford. Sporadic fighting broke out along the Chambersburg Pike and the Cashtown Road northwest and west of town, and slowly escalated as Buford deployed his dismounted cavalry along McPherson's Ridge. "General Lee and myself left his headquarters together,"recalled Longstreet, and had ridden three or four miles, when we heard heavy firing along Hill's front. The firing became so heavy that General Lee left me and hurried forward to see what it meant."29 Badly outnumbered, the Union troops nonetheless held ground stubbornly until 9:30 a.m., when the 1st Corps under Maj. Gen. John F. Reynolds arrived. Bringing on a general engagement went against Lee's orders, and he was by now baffled by the continued absence of Stuart. [Dick Anderson] found General Lee intently listening to the fire of the guns, and very much disturbed and depressed,"wrote Longstreet, referring to activities at 10 a.m. At length he said, more to himself than to General Anderson, "I cannot think what has become of Stuart; I ought to have heard from him long before now. He may have met with disaster, but I hope not. In the absence of reports from him, I am in ignorance as to what we have in front of us here. It may be the whole Federal army, or it may be only a detachment."30

It was not yet the whole Federal army. As the Union 1st and 11th Corps struggled west and north of town, A. P. Hill pushed west toward the town while Ewell approached from the north. Union Brig. Gen. James S. Wadsworth counterattacked and Reynolds, the Union commander of the field in lieu of Meade, was killed. The Federals recognized the importance of Cemetery Hill, a rise south of town, as they were pushed back and retreated through the town. "General Lee witnessed the flight of the Federals through Gettysburg and up the hills beyond,"wrote Walter Taylor. "He then directed me to go to General Ewell, and to say to him that, from the position which he occupied, he could see the enemy retreating over those hills, without organization, and in great confusion; that it was only necessary to press those people'in order to secure possession of the heights; and that, if possible, he wished him to do this."31

Lee established headquarters on the Chambersburg Pike in a series of tents across the road from the Mary Thompson House. The battle, now becoming a monstrous engagement as reinforcements poured in from both directions, continued to go well for the Army of Northern Virginia. A. P. Hill stopped his advance on Seminary Ridge, west of the town, but Ewell pressed southward through to the northern edge of Cemetery Hill. Although his army was not yet concentrated, Lee felt that once the major battle was underway even if he had not wanted it it must be pressed to shatter Meade's army. He therefore ordered Ewell to take Cemetery Hill "if practicable," the latter phrase a favorite of Lee's unfortunately vaguely leaving the order open to interpretation. Meanwhile, Edward Johnson approached Culp's Hill, a potentially commanding artillery position, but found it occupied.

Lee's plan now evolved further. He would sweep southward and attack the Union left, enveloping it and pushing northward. "When I overtook General Lee, at five o'clock that afternoon,"wrote Longstreet," he said, to my surprise, that he thought of attacking General Meade upon the heights the next day. I suggested that this course seemed to be at variance with the plan of the campaign that had been agreed upon before leaving Fredericksburg. He said, If the enemy is there to-morrow, we must attack him.'"32

Both armies massed around Gettysburg during the night, the Army of Northern Virginia assuming a north-south line along Seminary Ridge with Longstreet to the south and Hill to the north. The Federals formed a fishhook-shaped line around high ground on Cemetery Hill, Culp's Hill, and extending south to near the two highest elevation features in the region, Little Round Top and Round Top. Longstreet disagreed with his chief, preferring to fight a defensive battle. But Lee had made up his mind. "We were both engaged in company with Generals Lee and A. P. Hill, in observing the position of the Federals," John Bell Hood later wrote Longstreet." General Lee with coat buttoned to the throat, sabre-belt buckled round the waist, and field glasses pending at his side walked up and down in the shade of the large trees near us, halting now and then to observe the enemy. He seemed full of hope, yet, at times, buried in deep thought."33

By 11 a.m., a relatively late hour, the orders to attack were issued. By 3 p.m. the Confederate artillery opened fire. "So soon as the firing began," wrote Arthur J. L. Fremantle, "General Lee joined [A. P.] Hill just below our tree, and he remained there nearly all the time, looking through his field-glass, sometimes talking to Hill and sometimes to Colonel Long of his staff. But generally he sat quite alone on the stump of a tree. What I remarked especially was, that during the whole time the firing continued, he only sent one message and only received one report. It is evidently his system to arrange the plan thoroughly with the three corps commanders, and then leave to them the duty of modifying and carrying it out to the best of their abilities."34

Opportunities were present. The Round Tops were up for grabs. Moreover, Union Maj. Gen. Daniel E. Sickles moved his 3d Corps, against orders, out into an exposed salient through the Wheatfield and Peach Orchard. Longstreet's attack came at 4 p.m. Hood punched through the salient and captured a rocky feature known as the Devil's Den near the base of Little Round Top. About this time Union Maj. Gen. Gouverneur K. Warren discovered the open nature of Little Round Top and ordered it occupied. Uncoordinated attacks and counterattacks moved back and forth across various parts of the field. Ewell failed to attack until nearly dark, Johnson had no success at Culp's Hill, and Confederate casualties were heavy. Lee was clearly not at his best at Gettysburg, and in fact he was bothered intermittently by diarrhea and possibly a recurrence of malaria.35

That night the Federal high command decided to stay and fight another day. At daybreak on 3 July Longstreet pressed to move around the Yankee left and force Meade to attack. Lee was adamant about hitting the Yankees on Cemetery Ridge. Longstreet later recalled their early morning conference. "General,"said Longstreet, "I have had my scouts out all night, and I find that you still have an excellent opportunity to move around to the right [south] of Meade's army, and maneuvre him to attack us. He replied, pointing with his fist at Cemetery Hill, The enemy is there, and I am going to strike him.' I then felt that it was my duty to express my convictions; I said: General, I have been a soldier all my life. I have been with soldiers engaged in fights by couples, by squads, companies, regiments, divisions, and armies, and should know, as well as any one, what soldiers can do. It is my opinion that no fifteen thousand men ever arrayed for battle can take that position.'" General Lee then ordered Longstreet to prepare Pickett's division for attack.36

The Confederate attack would strike at the Union center, toward a copse of trees and an angle in a defensive stone wall. About 13,000 troops commanded by Maj. Gen. George E. Pickett, Brig. Gen. Johnston Pettigrew, and Brig. Gen. Isaac R. Trimble would make the charge across more than a mile of open ground, following a stiff artillery barrage designed to soften the Yankee defenses. The 159 Confederate guns opened at 1 p.m. and were answered promptly by Federal artillery from Cemetery Hill to Little Round Top. After an hour, the guns silenced, the Confederates assuming Yankee batteries were running low on ammunition. Then the charge began. It utterly failed. "All accounts of the charge agree that its failure began when the advance had covered about half the distance to the Federal line," wrote Porter Alexander, who directed the artillery. At that point the left flank of Pettigrew began to crumble away and the crumbling extended along the line to the right . . ."37

After ragged and bleeding troops stumbled back, Fremantle approached Lee. "His face, which is always placid and cheerful,"wrote Fremantle, "did not show signs of the slightest disappointment, care, or annoyance; and he was addressing to every soldier he met a few words of encouragement, such as all this will come right in the end.'"38 A short time later, he described the commander again. I saw General Wilcox . . . come up to him and explain, almost crying, the state of his brigade. General Lee almost immediately shook hands with him and said cheerfully, Never mind, all this has been my fault, it is I that have lost this fight, and you must help me out of it the best way you can.'"39 Meanwhile, Stuart had finally arrived and been repulsed east of the town by Federal Brig. Gen. David M. Gregg. Gettysburg was over, the Federal commander not pursuing even with his relatively fresh 6th Corps and the bulk of both armies in need of recovery. The Army of Northern Virginia had lost a devastating 28,000 men, about 1/3 of their force, while Meade lost 23,000, about 1/4 of his effective force.

For Lee, it was a defeat he would never fully recover from. That night, he met with a number of officers to plan the retreat. I ventured to remark, in a sympathetic tone, and in allusion to his great fatigue: "General, this has been a hard day on you,'"wrote John D. Imboden. He looked up, and replied mournfully, Yes, it has been a sad, sad day to us,' and immediately relapsed into his thoughtful mood and attitude."40

The following day, Lee wrote several missives, one of which constituted a short report to Jefferson Davis. Upon reaching the vicinity of Gettysburg, found the enemy and attacked him, driving him from the town, which was occupied by our troops," he wrote. "The enemy's loss was heavy, including more than 4,000 prisoners. He took up a strong position in rear of the town, which he immediately began to fortify, and where his re-inforcements joined him. On the 2d July, Longstreet's Corps, with the exception of one division, having arrived, we attempted to dislodge the enemy, and, though we gained some ground, we were unable to get possession of his position. The next day, the third division of General Longstreet having come up, a more extensive attack was made. The works of the enemy's extreme right and left were taken, but his numbers were so great and his position so commanding, that our troops were compelled to relinquish their advantage and retire. It is believed that the enemy suffered severely in these operations, but our own loss has not been light."

"General Barksdale was killed," he continued. " Generals Garnett and Armistead are missing, and it is feared that the former is killed and the latter wounded and a prisoner. Generals Pender and Trimble are wounded in the leg, General Hood in the arm and General Heth slightly in the head. General Kemper, it is feared, is mortally wounded. Our losses embrace many other valuable officers and men. General Wade Hampton was severely wounded in a different action in which the cavalry was engaged yesterday."41 He then wrote another long letter asking to be relieved of command. Davis did not take him up on this. On the same day, another setback befell the Confederacy when Vicksburg capitulated to Grant. It marked the beginning of a bleak period for Confederate morale, especially as life on the home front had become nearly intolerable with shortages, substitutions, and a downwardly spiraling economy. It was a burst for Yankee morale and cast a gloom over the Confederacy, yet the Confederate military machine remained viable and most of the Confederate states had not yet fallen into Northern occupation.42

On 13-14 July Lee finally retreated southward across the rain-swollen Potomac. "The General's anxiety was intense,"wrote Moxley Sorrel of the crossing. He expected to be attacked at the passage of the river. . . . General Lee, like every one, had been up the whole night, and his staff officers were stretched in sleep on the ground. . . . Just then a heavy gun was fired lower down, filling the gorge of the river with most threatening echoes. There,' said the General. I was expecting it, the beginning of the attack.'"43 But no attack came only a period of prolonged inactivity for the Army of Northern Virginia. In the wake of Brandy Station, where he had been wounded, Rooney was captured at Hickory Hill, near Hanover Court House. He was placed into Federal captivity near the site of the White House, his old home." I can appreciate your distress at Fitzhugh's situation,"Lee wrote Charlotte Wickham Lee from Culpeper Court House at month's end. I deeply sympathise with it, and in the lone hours of the night I groan in sorrow at his captivity and separation from you. But we must bear it, exercise all our patience, and do nothing to aggravate the evil."44

On 8 August Lee again attempted to tender his resignation. "Everything, therefore, points to the advantages to be derived from a new commander,"he wrote Davis, "and I the more anxiously urge the matter upon Your Excellency from my belief that a younger and abler man than myself can be readily obtained."45 Davis replied," I am truly sorry to know that you still feel the effects of the illness you suffered last Spring, and can readily understand the embarrassments you experience in using the eyes of others, having been so accustomed to make your own reconnaisances. . . . To ask me to substitute you by some one in my judgment more fit to command, or who would possess more of the confidence of the army or of the reflecting men in the country is to demand for me an impossibility."46 By 2 September, some were questioning Lee's continued popularity. The war clerk John B. Jones wrote, [Lee] rode out with the President yesterday, but neither were greeted with cheers. I suppose Gen. Lee has lost some popularity among idle street walkers by his retreat from Pennsylvania."47

While the situation was quiet in Virginia, matters were heating up in Tennessee and Georgia. Union forces under Rosecrans moved to occupy Chattanooga and threatened Gen. Braxton Bragg, south of the city in northern Georgia. Longstreet was ordered south to help support Bragg. The resulting battle along Chickamauga Creek was a tremendous Confederate victory, spurred by Longstreet's frontal attack that coincided with confused Union orders. My whole heart and soul have been with you and your brave corps in the late battle,"Lee wrote Longstreet, from near Orange Court House on 25 September. It was natural to hear of Longstreet and [D. H.] Hill charging side by side, and pleasing to find the armies of the East and West vying with each other in valor and devotion to their country."48 The Union army retreated in chaos to Chattanooga but regrouped to stun Bragg at Missionary Ridge and push him southward again in November.

During September and October Lee's health worsened. A severe cold exacerbated the rheumatism in his back. He experienced intense pain when riding his horse. By October his rheumatism was so severe that he was confined to his tent. For some time he could not mount a horse.49 I moved yesterday into a nice pine thicket, and Perry [a servant] is to-day engaged in constructing a chimney in front of my tent, which will make it warm and comfortable," he wrote Mary from Camp Rappahannock on 25 October. "I am glad you have some socks for the army. . . . I wish they could make some shoes, too. We have thousands of barefooted men."50

The Southern army was concentrated between Gordonsville and the Rapidan River. After minor operations and false starts on a new campaign, Meade moved south on 7 November. The stage for the Mine Run campaign was set. During mid-November Lee rode a fair amount but experienced sharp pains and remained stiff.51 He now took to staying inside a house rather than his customary tent. "The house General Lee occupied was a small frame structure on the side of the road and I found him already up and partially dressed, though it was still long before daylight."wrote William W. Blackford on 26 November. The room contained little else in the way of furniture than the General's camp bed, a small camp writing table and some camp stools. He was walking backwards and forwards in his shirtsleeves before a bright wood fire, brushing his hair and beard. . . . Well, Captain,' said he, what do you think they are going to do?' . . . I told him . . . attack. . . . He then resumed his walk and the brushing of his hair for a while and then faced me again and said, Captain, if they don't attack us today we must attack them.'"52

By late in the month Confederates were constructing winter quarters. Meade marched quickly ahead, crossed the Rapidan, and turned west against A. P. Hill and Ewell. But the plan unfolded more slowly and Confederates reacted, digging in defensive positions. At month's end Meade prepared to attack and then on 2 December Lee launched a turning movement of his own, but Meade had by then retreated. It was an unspectacular ending to a glorious summer of battle. In this last month of 1863 Lee seemed to age considerably and his hair and beard turned white. He still experienced a sharp pain intermittently, particularly on his left side.53 On 2 December he told Charles Venable, "I am too old to command this army; we should never have permitted these people to get away."54 Moreover, Mary's illnesses were deepening as well. I was grieved at the condition in which I found your poor cousin Mary [Custis Lee],"Lee wrote Margaret Stuart from Orange on Christmas Day. She is now a great sufferer. Cannot walk at all, can scarcely move."55

And then came a greater tragedy. Rooney was now imprisoned at Fort Monroe. And on 26 December Lee received a horrifying telegram, announcing the death of Rooney's wife Charlotte. "Custis'dispatch which I received last night demolished all the hopes in which I had been indulging during the day of dear Charlotte's recovery," Lee wrote Mary on 27 December. It has pleased God to take from us one exceedingly dear to us, and we must be resigned to his holy will. . . . What a glorious thought it is that she has joined her little cherubs and our angel Annie in heaven! Thus is link by link of the strong chain broken that binds us to earth, and smoothes our passage to another world."56

Library of Congress

National Archives and Records Administration

National Archives and Records Administration

National Archives and Records Administration

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

David J. Eicher