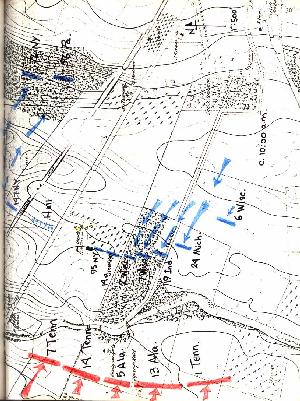

10:00 A.M

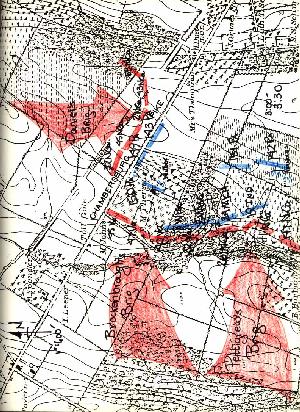

Buford, in the meantime, clattered down Washington Street, finding the inhabitants of this twice-visited town in a "terrible state of excitement"46 about the Rebel intruders. Directed out the Cashtown Pike, he saw no large hostile forces awaiting him, and pushed his troopers as far as the McPherson farm buildings and the ridge on which they set 47 (thereafter called McPherson's Ridge, although McPherson probably owned less of it than any other of his neighbors). Here they halted and sized up the decoy, Buford keeping a rein on those who may have been eager to pursue the all-too-willing Confederate regiment. His ploy not producing the expected results, Pettigrew went back to his divisional commander and reported what his pickets saw as a reason for returning with fifteen empty wagons. Heth was determined to get "those supplies" and was granted permission by his corps commander to proceed to Gettysburg at first light on the morrow. Hill summarily ordered Pender to follow closely at Heth's heels as a support, and ordered Anderson to march early so he could also be in supportive distance.

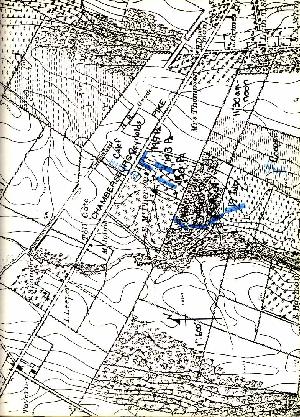

Buford was making his own arrangements to meet what he must have thought inevitable. During

the afternoon, he nursed his thin line of cavalrymen until he was sure it was healthy enough to withstand

repeated attacks by any Confederate force. Devins' Second Brigade was deployed

26

from near the Cashtown Pike at Willoughby Run to the Mummasburg road and then out to the York Pike.

Gamble's First Brigade was all around the McPherson Farm, extending from the Cashtown Pike to the

Hagerstown Road.48 Grasping the tactical importance of the McPherson Ridge and its neighboring Seminary

Ridge as a defensive position, Buford was sure that his veterans could hold off a Confederate assault long

enough until the Union First and Eleventh Corps of infantry and artillery could come up. Reynolds' First

Corps was encamped about five or six miles south of Gettysburg near where Marsh Creek crossed the

Emmitsburg Road, within supporting distance if things got too hot.

Slentz did not care about the tactical importance of his farm; his crops and fencing were pre-eminent

in his thoughts that Tuesday night. He watched helplessly as men and their horses trampled oats and wheat,

tore down his fencing for firewood and for possible use as breastworks on the morrow, and looked on his

turkeys, chickens, hogs, and cows with ravenous eyes. After watching Buford's troopers cut and throw down

about a quarter mile of post and rail fence "to make way for the battle" and another cord of rails used up for

firewood 49 Slentz decided he would not desert the farm and leave it in the hands of these soldier-vultures

(North or South). Besides his own personal property, he had an obligation to protect the real estate of his

absent

27

landlord. The family (John and Eliza, particularly) must have spent a restless and sleepless night wondering

about the morning's possible threat to their pastoral lives.

When the first shots were exchanged on the picket line shortly after dawn, the family was aroused

by the noise. When it was apparent that Heth's Division was going to be fully committed to an assault on

primarily Gamble's front, Buford tightened his line so that Gamble's Brigade (ca. 1200 men) line ran from

the unfinished railroad bed to the Hagerstown Road on the left, and Devin's Brigade was pulled in so that it

joined Gamble's right flank at the railroad and extended to the Mummasburg Road.50 It was about this time

that a 3-inch rifle of Marye's Fredericksburg Battery unlimbered in the Cashtown Pike near Blocher's

Schoolhouse and sent a shell toward the Union soldiers visible on the ridgeline ahead. This first shot burst

ineffectively high above the heads of the cavalrymen, and Marye had the gun crew fire several more shells

"in rapid succession, receiving no immediate response".51 But soon Calef's Battery A, 2nd U.S. Artillery

(which came up with Buford's two brigades) answered these shots, its first round ordered by Buford himself.

Troublesome civilian affairs prevailed on Buford's time next. He ordered Slentz to get his family out

of the field of danger while he could. Needless to say, all must have been confusion for the

28

beleaguered family. There was no time to pack clothes or load a wagon with household goods,52 and when

the farmer tried to herd the livestock in the direction of Round Top or Culp's Hill,53 they were so spooked by

the sounds of gunfire, smell of gunpowder, and general mass confusion that he had to give up the idea and

leave them to their fate. The family itself left with nothing but the clothes on their backs. The five children

were barefooted and bareheaded, and Eliza left baking bread in the oven in her hurry to leave.54 Before they

could reach the town, however, the battle warmed up considerably and caused them to seek refuge in "the

cellar of the 'Seminary"', where they would remain for the three days of the battle. 55 McConaughy's

begrudging of the building of the turnpike back in 1815 came back to haunt Slentz almost fifty years later.

The turnpike brought both forces to clash on his farm. Had it not been there, the battle may have swept

around the farm and not gone directly through it.

Davis's and Archer's forces, meanwhile, had met stiff resistance from Buford's dismounted

cavalrymen and were temporarily checked until

29

the timely appearance of Wadsworth's Division of the Union First Corps. The lead brigade, commanded by

Lysander Cutler, consisted of five regiments, and was accompanied by Hall's 2nd Maine Battery. The head

of the column dashed across the Cashtown Pike and then across the railroad bed. Here the 76th New York

(the lead regiment) supposedly held its fire so that the 56th Pennsylvania could come up beside it and have

the honor of firing the first infantry shot from its native soil, a chivalrous and foolish gesture certainly not

encouraged by the corps commander. John Reynolds was professional army, and would have been appalled

had he noticed that kind of parade-ground maneuver.Davis also seemed to have been unimpressed by the right wing of Cutler's Brigade (the 76th and

147th New York, and the 56th Pennsylvania) but attacked with great spirit, causing Cutler to order the wing

back to the ridge and woods behind it. The 147th New York, across the railroad cut and directly opposite

Hall's Battery, did not immediately get the order and was almost captured wholesale when the two regiments

on the right fell back. Extricating itself just in time, this time the 147th was guilty of retreating without

informing the now unsupported battery to its left. Hall discovered just in time that he was alone north of the

Cashtown Pike and was the object of Davis's attack as his men entered the cut, climbed its slopes, and started

dashing to the rifled pieces. Wheeling his right section to the north as speedily as possible, Hall fired

quickly, but his rifles (more effective at longer ranges) would never hold back Davis's Mississippians and

North Carolinians. Davis's Brigade, consisting of only three regiments on July 1, met the three regiments of

Cutler's right wing and Hall's Battery and completely

30

32

33

33 immediately ran into Archer's Brigade.

The so-called Iron Brigade consisted of about 1800 men as it entered the battle,57

Midwest men in black hats whose reputation for fighting ability was well known in both armies.

Arriving on the battlefield to the sound of the guns, the brigade turned west off the Emmitsburg

Road and obliqued towards the seminary. The members of the Sixth Wisconsin were dis-

appointed. They had hoped to march through the town, their band playing "The Campbells are

Coming", and impress the Gettysburg residents with their parade-ground appearance.58 There

was no time for that bit of showiness, as the brigade commenced the double-quick as soon as they

reached the crest of Seminary Ridge. There was also no time to stop and load the muskets, so the

soldiers loaded on the run. The brigade entered Herbst Woods with the 2nd Wisconsin in the lead

on the right as they advanced en echelon. They had not gone thirty yards into the woods before

they came under fire of Archer's Brigade. The 2nd Wisconsin, being in the lead, was most heavily

hurt by this fire--Colonel Lucius Fairchild severely wounded and losing his left arm, Lieutenant-Colonel George Stevens killed--their loss greater than any of the other Iron Brigade regiments

because "the Confederate soldiers

immediately ran into Archer's Brigade.

The so-called Iron Brigade consisted of about 1800 men as it entered the battle,57

Midwest men in black hats whose reputation for fighting ability was well known in both armies.

Arriving on the battlefield to the sound of the guns, the brigade turned west off the Emmitsburg

Road and obliqued towards the seminary. The members of the Sixth Wisconsin were dis-

appointed. They had hoped to march through the town, their band playing "The Campbells are

Coming", and impress the Gettysburg residents with their parade-ground appearance.58 There

was no time for that bit of showiness, as the brigade commenced the double-quick as soon as they

reached the crest of Seminary Ridge. There was also no time to stop and load the muskets, so the

soldiers loaded on the run. The brigade entered Herbst Woods with the 2nd Wisconsin in the lead

on the right as they advanced en echelon. They had not gone thirty yards into the woods before

they came under fire of Archer's Brigade. The 2nd Wisconsin, being in the lead, was most heavily

hurt by this fire--Colonel Lucius Fairchild severely wounded and losing his left arm, Lieutenant-Colonel George Stevens killed--their loss greater than any of the other Iron Brigade regiments

because "the Confederate soldiers

It was during this countercharge by Meredith's Iron Brigade that Major-General John Reynolds was

killed. Reynolds' style of command placed emphasis on personal command and personal direction, and he

was at the edge of Herbst Woods directing the deployment of the brigade and watching for the advance of

Doubleday's Division when he was caught from behind by a Confederate bullet. Doubleday had arrived on

the field before his division, since he was in temporary command of the First Corps in its entirety while

Reynolds was in overall command of operations on the field of battle. Reynolds, seeing the Confederate line

extend southward into the Herr Ridge Woods, believed that Lee's army was attacking on a front which

extended from the Cashtown Pike on the north to the Hagerstown Road on the south. He directed Doubleday

to concentrate all his available troops to cover the Hagerstown Road, while he would guard the Cashtown

road with Cutler's Brigade until the rest of the corps arrived.60 Doubleday saw Herbst Woods as the key to

fulfilling these orders, since Confederate troops could not pass up either the Cashtown or the Hagerstown

roads without risking a flanking fire from the Union First Corps.

36

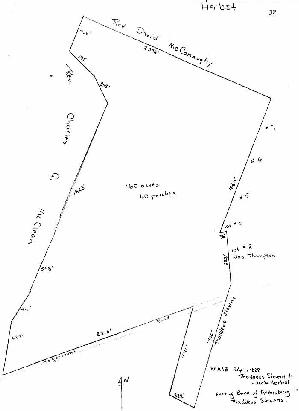

10:30-11:30 A.M.

the run within about twenty minutes after their collision with those black-hatted fellows

of the Army of the Potomac. Willoughby Run proved to be an ally of the Union, however, its

brush-and-tree-lined banks and the run itself proving to be a retardant to an orderly retreat.

Archer, appearing greatly fatigued, was captured along with between 75-200 others who were

either too slow in making the crossing or were hampered by terrain features. 62 This incident and

ensuing events were recalled by a veteran of the 2nd Wisconsin:

the run within about twenty minutes after their collision with those black-hatted fellows

of the Army of the Potomac. Willoughby Run proved to be an ally of the Union, however, its

brush-and-tree-lined banks and the run itself proving to be a retardant to an orderly retreat.

Archer, appearing greatly fatigued, was captured along with between 75-200 others who were

either too slow in making the crossing or were hampered by terrain features. 62 This incident and

ensuing events were recalled by a veteran of the 2nd Wisconsin:We followed closely upon their heels, and, crossing the run about a moment later captured General Archer and several hundred of his men who had taken shelter behind a clump of willows. In the charge across the Run this willow-clump, very compact and interwoven, divided the second regiment into two parts. . . . The left division was led by Captain Charles Dow, and to him General Archer surrendered and offered his sword. But Captain Dow replied: "Keep your sword, General, and go to the rear; one sword is all I need on this line." So General Archer passed in front of the willow-clump toward our right before crossing to the rear. . . .

Just as General Archer and his captured men were crossing the Run to the rear, under a hastily improvised guard, and it became certain that we had won the first heat of battle, a sergeant of our company, Jonathan Bryan by name, was shot through the heart by a Confederate from the edge of the woods beyond a field in our front, while waving his hat and cheering for victory. . . . Comrade Bryan was the only man of our regiment killed west of Willoughby Run. 63The Confederate advance being checked south of the Cashtown Pike, it was almost concurrently halted and thrown back north of the pike, too. When Davis's 2nd and 42nd Mississippi regiments outflanked the right wing of Cutler's Brigade, causing them to fall back to the "Oak Ridge'' line, Hall's Battery was uncovered and offered as an all-too-tempting target. And, beyond, were the two left regiments of Cutler's Brigade who, like Hall, were offering their flanks to Davis for enfilading. This demi-brigade was commanded by Colonel Edward B. Fowler of the 84th New York (14th Brooklyn) and consisted of the 14th Brooklyn and the 95th New York. Fowler, like Hall, was taken by surprise when the right of Cutler's line fell back. The first he knew of it was when his own right was subjected to an enfilading fire from Davis's Mississippians across the pike. Fowler ordered the two regiments to fall back to the cover afforded by the McPherson farm buildings, especially the imposing stone bank barn. From there the two units changed front to the north and attacked Davis before he could cross the pike.

40

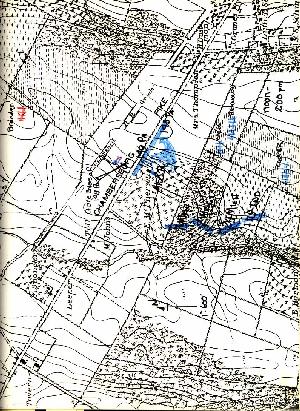

Doubleday, seeing the Mississippians cross the railroad grading at the same time as

Fowler noticed them, ordered Rufus Dawes to take his reserve regiment of the Iron Brigade and

attack Davis.  What looked like a sacrificial effort on the part of Dawes and his 6th Wisconsin

became another bright spot for the Army of the Potomac that forenoon. Fortunately for

Doubleday and Dawes, Fowler was as courageous as he was intelligent, and did not retreat to the

ridgeline as Cutler had wanted him to do. Instead, Fowler and Dawes wound up attacking Davis

with as much unity and synchronization as if it had been planned all along.

Not expecting this sudden counterattack the Mississippians fell into disorder and retreated back to

the railroad bed to seek shelter in the cuts created there by the terrain features of the ridgelines. The "shelter"

became an entrapment, as Fowler's men lined the south side of the cut and fired down into the crowded mass

at the same time that Dawes brought part of his 6th Wisconsin into the cut (near present Doubleday Avenue

extended) and fired down the railroad bed. This brought Davis's men into a murderous cross-fire and

magnified the hopelessness of their situation. Out of humanity, the Yankees stopped firing, with one accord

and demanded surrender. Most of the 2nd Mississippi surrendered to Dawes, while many of the 42nd

Mississippi gave themselves up to the New Yorkers. Probably just as

What looked like a sacrificial effort on the part of Dawes and his 6th Wisconsin

became another bright spot for the Army of the Potomac that forenoon. Fortunately for

Doubleday and Dawes, Fowler was as courageous as he was intelligent, and did not retreat to the

ridgeline as Cutler had wanted him to do. Instead, Fowler and Dawes wound up attacking Davis

with as much unity and synchronization as if it had been planned all along.

Not expecting this sudden counterattack the Mississippians fell into disorder and retreated back to

the railroad bed to seek shelter in the cuts created there by the terrain features of the ridgelines. The "shelter"

became an entrapment, as Fowler's men lined the south side of the cut and fired down into the crowded mass

at the same time that Dawes brought part of his 6th Wisconsin into the cut (near present Doubleday Avenue

extended) and fired down the railroad bed. This brought Davis's men into a murderous cross-fire and

magnified the hopelessness of their situation. Out of humanity, the Yankees stopped firing, with one accord

and demanded surrender. Most of the 2nd Mississippi surrendered to Dawes, while many of the 42nd

Mississippi gave themselves up to the New Yorkers. Probably just as

41

many, however, made good their escape by throwing down their arms and running west through the cut and

scaling the embankments and heading for the Confederate lines through the high-growing wheatfield north

of the railroad grading.

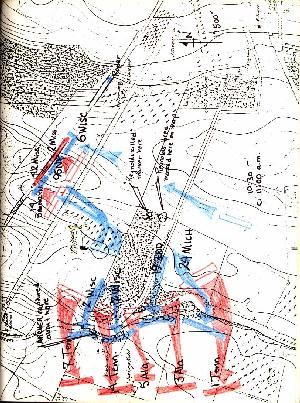

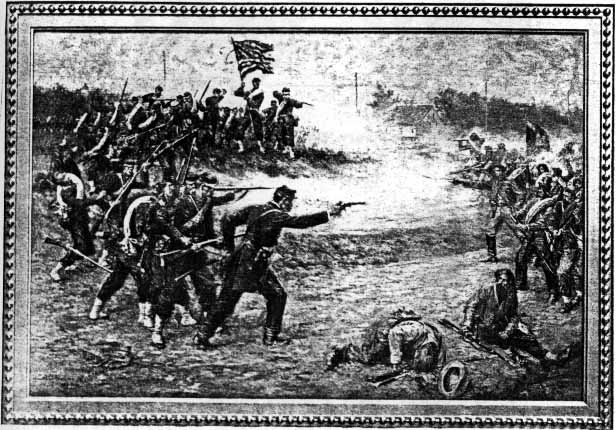

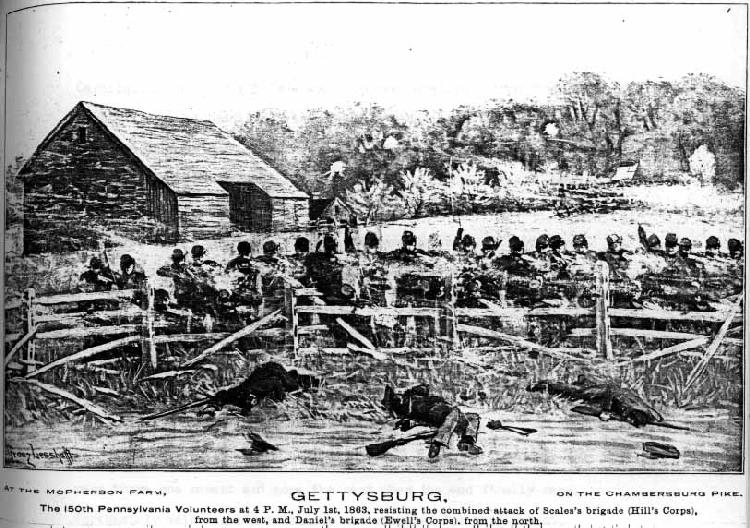

REPRODUCTION FROM AN OIL PAINTING BY A. C. REDWOOD 64

Showing the Fighting Fourteenth in action in the Railroad Cut at Gettysburg, Pa, July 1, 1863, at, which

time Davis' Mississippi Brigade was captured

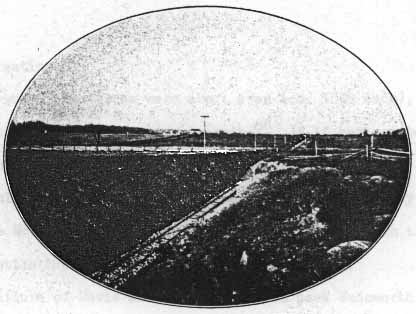

Railroad Cut, early view (c. 1864) 65

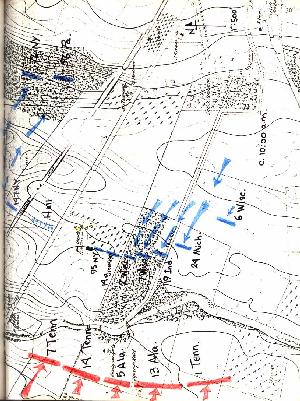

McPHERSON'S FARM

Showing Railroad Cut and Chambersburg Pike

View looking west from Oak Ridge, c. 1880s 67

44

At the cut, where the forces were about even (ca. 1000 each), Davis's Brigade was mysteriously understrength. 68If it had not been for the unfavorable position that the Mississippians fell back to, they probably would have made good their escape. It was extremely fortunate for the Northerners that Davis's men obliged them with the opportunity to bottle them up and "shoot fish in a barrel". After the failure of Davis and Archer to press back Wadsworth's Division, there was about a two-hour lull in the infantry fighting on and about the McPherson Farm. Heth, surprised by the determined resistance of the Federals, decided to wait until Pender's Division came up to support him before he would resume his attack. Colonel Henry Burgwyn of the 26th North Carolina was impatient to attack, believing Hill and Heth to be wasting precious time by waiting for the remainder of the Confederate Third Corps to arrive. 69Doubleday could only be getting stronger during this same lull, and the 26th North Carolina, part of Pettigrew's Brigade, was fresh and eager to attack those battle-weary troops already decimated by Archer and Davis. But, now that it was too late, Heth wanted to be cautious.

45

Doubleday, in the meantime, still in command of the Union First Corps, was relieved

at the approach of two brigades of his own division--Roy Stone's "Bucktail Brigade" and

Chapman Biddle's Brigade. In order to form a united front, the Iron Brigade was ordered back to

the east side of Willoughby Run, its line reshuffled so that the most severely injured regiments

held interior positions and did not guard the vital flanks.  Biddle's Brigade was given the

assignment of guarding the approaches from the Hagerstown Road, and were placed on the

Herbst Farm south of the woodlot. The four regiments of the Iron Brigade stayed in Herbst

Woods, and Stone's Brigade occupied the area around the McPherson farm buildings. Doubleday

was set on defending the ridges and holding his position, and "was in favor of making great

sacrifices" in order to assure this end. He was convinced that extraordinary measures were

necessary since "Gettysburg covered the great roads from Chambersburg to York, Baltimore, and

Washington, and . . . its possession by Lee would materially shorten and strengthen his line of

retreat." 70

Biddle's Brigade was given the

assignment of guarding the approaches from the Hagerstown Road, and were placed on the

Herbst Farm south of the woodlot. The four regiments of the Iron Brigade stayed in Herbst

Woods, and Stone's Brigade occupied the area around the McPherson farm buildings. Doubleday

was set on defending the ridges and holding his position, and "was in favor of making great

sacrifices" in order to assure this end. He was convinced that extraordinary measures were

necessary since "Gettysburg covered the great roads from Chambersburg to York, Baltimore, and

Washington, and . . . its possession by Lee would materially shorten and strengthen his line of

retreat." 70

Although infantry fighting was recessed at this time, artillery duels continued and even intensified as

Wainwright's First Corps artillery was brought up. On Herr's Ridge opposite, Pegram's and McIntosh's

Artillery Battalions exchanged shots with Wainwright, but could not pass up the opportunity to shell the

unprotected Union infantry

46

on McPherson's Ridge, especially the men of Stone's Brigade. This brigade had been deployed so that the

150th Pennsylvania was slightly to the left and front of the 149th Pennsylvania, in the orchard south of the

McPherson barn, 71while the 149th lay in the lane fronting the barnyard 72 with part of its right flank facing

northward at right angles, south of the Cashtown Pike. The 143rd Pennsylvania was behind these two, with

its right near the stone barn and its left extending southerly in the direction of Herbst Woods. 73

These soldier boys would have grimaced had they known later-day historians would refer to those

two hours (before the Confederates resumed their infantry attacks) as a "lull". Artillery shells were flying

thick and fast from the west, and within a short while, they were subjected to an enfilading fire from the

north, also. 74 Long range musketry and sharpshooting fire from the direction of Herr Ridge and Oak Hill

continued unabated during those two hours. The 143rd Pennsylvania, in rear of the 150th and 149th

regiments, was not allowed to return the musketry fire for fear of striking their own

47

11:30 - Noon

48

troops. While standing under this bothersome fire "in line near the barn a bullet struck Jacob Yale above the

eye. . . . This was the first man killed of Company I, One Hundred and Forty-Third Pennsylvania

Volunteers." 75

The infantry was not isolated on McPherson's Ridge--yet. Fresh Union batteries relieved Hall after

he was driven out by Davis's attack. Cooper's Battery B, 1st Pennsylvania Light Artillery joined Biddle's

Brigade on the ridgeline south of the Herbst Woods. When the cannon of McIntosh and Pegram opened

from Herr's Ridge, Cooper's six 3-inch rifles responded in kind, and he was immediately reinforced by

Battery L, lst New York Light Artillery, commanded by Captain Gilbert Reynolds. Calef's Battery was

likewise recalled and both Calef and Reynolds took position north of McPherson's barn on a line towards the

railroad cut. Fronting to the west, like Stone's infantry brigade, these batteries suffered initially when they

were enfiladed about 1:00 P.M. by Carter's and Fry's Batteries on Oak Hill, and soon joined by Brander's

Battery on Wills's Farm, all three north of the McPherson Farm.

The results of the Confederate fire from the north were immediate. Calef and Reynolds could not

withstand a cross-fire from west and north, so changed position altogether. The two batteries crossed the

Cashtown Pike, withdrew from the McPherson Farm, and used Herbst Woods to cover

49

50

them from Hill's battalions on Herr's Ridge. Fronting to the north, they, with Cooper's Battery, concentrated their fire on those newly arrived batteries of the Second Corps and Brander's Battery. The Union infantry likewise had to make adjustments to survive this cross-fire. The 150th Pennsylvania crowded into the area south of the McPherson barn 76 so as to use its massive stone walls for protection. The 149th Pennsylvania, up to that time fairly secure behind the ridgeline in McPherson's lane, now suffered like her sister regiments:

Close on to 1 P.M. the scene changed. The enemy's reinforcements were now arriving on the field. The first intimation we had of it was the fire of one of their batteries (Carter's) stationed on Oak hill north of us. The crash of a shell through the tops of the old cherry trees along the lane admonished our commander that we were exposed to an enfilade fire which might do us great damage. He at once swung our left out on the pike in line with the right, and ordered a side-step movement to bring as much of the regiment as possible into the shelter of the dry ditch on the southern side of the pike, in which we lay down. We were now comparatively safe from the battery on Oak hill, but, un- fortunately, the enemy to the west got a glimpse of our left before we lay down, and shrewdly guessing our position, at once commenced to drop shells into our ranks over the crest of the ridge. . . .The 143rd Pennsylvania was moved to the right of the 149th Pennsylvania, so that Stone's Brigade line was .........

51

to the west just south of the McPherson barn, and the 149th and the 143rd fronting northward on the south

side of the Cashtown Pike.

Frustrated at his inability to do something to stop the artillery pounding, Colonel Stone hit upon a

scheme which he hoped would spare the brigade further shelling. It was his proposal that the flags of a

regiment might be used to deceive the Confederate gunners and draw the fire away from the brigade. The

colors of the center regiment, and that one under the most galling fire, were chosen for this experiment.

Color Sergeant Henry G. Brehm thereupon advanced his color guard 78 with the state and national colors of

the 149th Pennsylvania, across the pike at the direction of Lieutenant-Colonel Walton Dwight. The position

occupied by the guard was now some fifty yards on the other side (north) of the pike, south of the railroad

cut's greatest depth by about 100 yards, and to the left front of the left of the regiment. (Approximately

where the Reynolds equestrian monument is now located.) Here the squad took advantage of a pile of rails

stacked as breastworks by Buford's troopers. The rails were carried from a fence bounding the eastern edge

of a wheatfield which sloped westward down the ridge between the railroad grading and the turnpike. The

squad was comparatively safe behind this rail-pile, which was placed so

52

that one pile faced north and the other west, forming a right angle. 79

In this position our flags were plainly visible over the standing wheat, to the battery west of us, but the rail piles and men behind them were hid from their view; and, evidently thinking that the regiment had changed front, they now diverted their fire in that direction. Stone's ruse had succeeded. 80About 2:00 P.M. the brigade had more to worry about than the artillery fire of far-off batteries. Most of the brigade, forced to silently bear the shelling, had to content itself with firing a few rounds of long-range musketry to ease its sense of helplessness. A corporal in the 143rd later described his own participation in this phase of the battle:

We saw no enemy except men at a very great distance away. However, I fired with the rest, according to orders, and proceeded to put the powder from two cartridges into my gun and rammed a ball down on the double charge. I then raised the sight to 900 yards and fired at some rebels whom I saw away off on the hill, probably a mile distant. 81There were Confederate troops "much nearer at hand" very shortly, the 143rd Pennsylvania was called upon to protect the right flank of Dwight's 149th infantry regiment as the latter was hurriedly advancing to the railroad grading. North of the railway and closing fast on the Cashtown Pike was part of Daniel's Brigade (2nd and 45th North Carolina). Two "most effective" volleys from Dwight's infantry,

Dwight led his men back to the safety of the dry ditch along the pike. 82

Stone was wounded during this second action at the railroad cut, and the command of the brigade

devolved upon Colonel Langhorne Wister of the 150th Pennsylvania. Stone was carried into the stable area

of the McPherson barn to receive "first aid" treatment until he could be evacuated. 83

Dwight led his men back to the safety of the dry ditch along the pike. 82

Stone was wounded during this second action at the railroad cut, and the command of the brigade

devolved upon Colonel Langhorne Wister of the 150th Pennsylvania. Stone was carried into the stable area

of the McPherson barn to receive "first aid" treatment until he could be evacuated. 83

Daniel, witness to the repulse of the 2nd and 45th North Carolina regiments, ordered the three

remaining regiments of his brigade (the 32nd, 43rd, and 53rd North Carolina infantry regiments) to attack

the "regiment" by the cut, seeing the 149th's standards still there. The only troops that Daniel could see at

that time were companies of

54

2:00-2:30 P.M.

55

the 150th Pennsylvania, which had advanced across the pike towards the cut on orders of

Lieutenant-Colonel H. S. Huidekoper, then in command of the 150th. The remainder of the

regiment had come out from behind the McPherson barn to join the left of the 149th

Pennsylvania behind the post and rail fence paralleling the south side of the pike. 84 Daniel

was confused, believing the six companies to be enticing him into a trap wherein he would

be flanked by the "regiment" whose colors he saw near the cut. Pressing on cautiously

towards the grading he was once again fired upon by two volleys and attacked with the

bayonet by Huidekoper's six companies, led in person by Wister. 85 The element of surprise

in doing the unexpected once again spoiled Daniel's plans, and these two regiments on the

left (the 43rd and 53rd North Carolina) ran away from the crazed bucktails.

Resumption of Hill's attack towards Willoughby Run at this moment caused Huidekoper to

order the six companies back to the regiment, which still remained at the post and rail fence firing at

Daniel, in conjunction with the 149th and 143rd Pennsylvania Volunteers. The Bucktail Brigade

brought a third halt to Daniel's attempt to gain the Cashtown Pike. The three regiments had managed

to foil a flanking

from behind the McPherson barn to join the left of the 149th

Pennsylvania behind the post and rail fence paralleling the south side of the pike. 84 Daniel

was confused, believing the six companies to be enticing him into a trap wherein he would

be flanked by the "regiment" whose colors he saw near the cut. Pressing on cautiously

towards the grading he was once again fired upon by two volleys and attacked with the

bayonet by Huidekoper's six companies, led in person by Wister. 85 The element of surprise

in doing the unexpected once again spoiled Daniel's plans, and these two regiments on the

left (the 43rd and 53rd North Carolina) ran away from the crazed bucktails.

Resumption of Hill's attack towards Willoughby Run at this moment caused Huidekoper to

order the six companies back to the regiment, which still remained at the post and rail fence firing at

Daniel, in conjunction with the 149th and 143rd Pennsylvania Volunteers. The Bucktail Brigade

brought a third halt to Daniel's attempt to gain the Cashtown Pike. The three regiments had managed

to foil a flanking

56

movement of five regiments; for the third time that day Union troops on the McPherson Farm and in Herbst Woods had met Confederate brigades in battle and defeated each one in turn--Archer's, Davis's, and Daniel's.

This time, however, Hill did not give the Union troops an opportunity to concentrate on one

brigade at a time. He sent forward Brockenbrough's Virginians on the left (whose attack would be

concentrated southward from the pike to Herbst Woods) and Pettigrew's North

57

Carolinians on the right (who would oppose Meredith's Iron Brigade in Herbst Woods and

Biddle's Brigade on the ridge beyond). Wister was severely wounded in the face and mouth as

Brockenbrough closed in from the west and was forced to relinquish command of the brigade when he

was prevented from giving orders due to the "lacerated and swollen condition of his mouth and face".

He remained on the field, however, "doing what he could by his presence and example to animate the

men". 86 Huidekoper was also wounded at this time, leaving the field momentarily to go to the

McPherson barn in search of emergency treatment in applying a tourniquet to and bandaging his

shattered right arm. 87 His regiment, except for companies A, F, and D, 88 now concentrated on the

Confederates advancing from the west.

Numbers finally overwhelmed the Yankee defenders. The units were there one moment and

gone the next when the end finally came. Fortunately Wainwright's artillery had prepared for this

moment. All First Corps batteries were placed on the Seminary Ridge to provide a rallying point.

Only Reynolds' Battery L of New York was now in the actual field of combat. Four pieces were south

of Herbst Woods assisting Biddle's Brigade, while one section under Lieutenant Wilber was in

Slentz's orchard trying to help the 150th Pennsylvania

58

59

and the other two regiments of the brigade, as well as the Iron Brigade. 89 These

sections of Reynolds' New York Battery L were obliged to fall back before the infantry did

in order to save themselves.

The suddenness of the Union withdrawal was recounted by two participants. A member of

the 150th Pennsylvania left the regimental line near the quarry to assist in bringing in the wounded

Major Thomas Chamberlin, shot down when the 150th moved from its position along the pike to front

westward:

The suddenness of the Union withdrawal was recounted by two participants. A member of

the 150th Pennsylvania left the regimental line near the quarry to assist in bringing in the wounded

Major Thomas Chamberlin, shot down when the 150th moved from its position along the pike to front

westward:

. . . when the movement was completed, Lt. Col. Huidekoper discovered the loss of the Major, and called for volunteers to bring him in, five of us went out and got safely back with him. . . . We carried him into the McPherson house which stood in rear of our line, and can never forget the gallantry displayed by him on that occasion; he was badly wounded, (we thought at the time mortally) and when we laid him down on the floor, he addressed us in these words: "Now boys, raise my head up, give me a drink of water & go out to your work". When we came out of the house, I stopped at the pump to fill my canteen & then started toward the place where I had left the Reg't, but it must, in the meantime, have changed front again to the north, at any rate it was not where I had left it; seeing Weidensaul, 90 Orderly Sergt of Co. D. I said to him: "Where is the Reg"? his reply was, "to hell with the Regt, let us go over there," referring to a vacancy which existed between the left of the 149th & the barn, and toward which the rebels were advancing; he and I and a number of others of our Regt, ran over and threw

ourselves into the dry ditch on the south side of the road and opened fire, and there remained until the whole line fell back. After this time I cannot give positions of the 150th as we were all mingled together, and it seemed to me that every man was fighting on his own hook. . . . We slowly fell back, firing as we went, and at the bottom of the slope again halted and formed a line, and when the rebels came over the brow of the hill we gave them a volley, which, for the moment, staggered them, then we charged up the slope, but we were forced back and crossed the valley below the Seminary. . . . 91

The other participant was one of the color guard of the 149th Pennsylvania, still on assignment in advance of the pike with the state and national colors. The decoy colors were never ordered to return to the regiment, even after the three repulses of Daniel. Although Stone ordered them to the advance post, and should have been responsible for bringing them back in, he was wounded and no longer on the field of battle (lying within the stone walls of the McPherson barn). Wister had likewise been wounded. Why Colonel Edmund Dana, who commanded the brigade at the end, forgot about six men and two flags when the world was disintegrating all around him is understandable. But why Lieutenant Colonel Dwight did not see to their safety is another matter. They were Dwight's men and flags. The most commonly accepted theory is that Dwight was more confused than Stone, Wister, or Dana because his mind was clouded by liquor during this battle. 9261

These Confederates had crawled on their hands and knees through the high wheat to escape

detection, and succeeded in completely surprising the color guard of the 149th Pennsylvania. When they

sprang at the rail-pile with a rebel yell they startled the guard to its feet, Sergeant Brehm (with the national

colors) colliding with Corporal Frank Lehman (who had the state flag). Lehman fell to his knees. A

Southerner grabbed the flagstaff while another aimed his musket at Lehman's head from across the rails.

Lehman got hold of the musket barrel, just in

62

time to deflect the Confederate's aim, while Corporal Spayd shot the assailant at the same

moment. Lehman's attention naturally absorbed by the struggle to preserve his own life, lost hold

of the colors,

. . . when startled by the rebel yell they had barely time to jump to their feet when the enemy was right by them; that one of them laid hold of the National flag in the hands of Brehm, saying "this is mine;" that Brehm said "no by G-- it isn't," seized him by the throat and threw him on the ground, but the Sergeant went down on top of him; that evidently the rebels had not expected any resistance, and so, in the anxiety of each one to get one of our flags, they were unprepared for the hot reception given them and which gave our men the advantage; that in a few seconds, the guard having shot the majority of their assailants, and clubbed others, Brehm was on his feet again with the colors and running at the top of his speed for the regiment, and that he (Friddell) and another comrade (Hammell) were following close behind; that they got near the Confederates along the lane before discovering amid the smoke of battle, that they were men in gray; that Brehm dashed right through their line, but [Friddell] and a comrade were shot down in the lane in a struggle with the enemy. 93Captain Bassler, commander of the color guard, was lying wounded in the southeast corner of the McPherson barnyard, and saw his sergeant running at an angle through the meadow on the east side of the lane, evidently attempting to reach his own troops near the seminary. Brehm, like Spayd, became an appealing target for the men of the 55th Virginia who saw him cut in front of them at the lane "all alone, with long strides, and the colors at a right shoulder shift". 94 It was only moments before he was brought down, the national flag snatched away from him as the trophy of J. T. Lumpkin of Company C, 55th Virginia. 95

64

A second casualty, falling within sight of the present bronze memorial to Burns, was divisional

commander Major-General Henry Heth. Heth, hit by a ball fired from the vicinity of the McPherson barn (by

one of those Bucktails fortified within the barn?), fell unconscious, and feared dead by his men. Struck on

the left side of the forehead, the bullet penetrated to the bone, and knocked him out for more than

a day. Heth recovered, however, and later recounted that he "would have been killed but for having put on a

new hat that morning so much too large that he had the lining stuffed with a thick package of foolscap paper

in his haste and this broke the force of the ball and saved his life." 100

47 Jacobs, p. 22.

48 Major Hillman A. Hall, et al., History of the Sixth New York Cavalry (Worcester, Massachusetts,

1908), p. 134.

49 Slentz claims.

50 Hall, p. 134.

5l Lt. John L. Marye, "The First Gun at Gettysburg, With the Confederate Advance Guard'", The

American Historical Register (July, 1895), p. 1229.

52 Why Slentz wasn't better prepared to quickly abandon his home is an intriguing question. For two

days his farm had seen Union and Confederate soldiers, and two whole cavalry brigades encamped right

under his nose the previous afternoon and evening. Why he did not foresee hostilities or the possibility that

his family would be evicted by the armies is incomprehensible.

53 Many farmers took their horses and cattle to Culp's Hill and Round Top, where they presumed they

would be safe from Union and Confederate rustlers or rustlers' bullets and shells.

54 Nothing must have interfered with this farm wife's morning routine!

55 Recalled by the former Sarah Slentz while reading a Phoenixville, Pa. 1880s account by her mother.

"Local Woman Fled with Mother to Seminary Here", 1938 Newspaper Clipping, GNMP vertical files.

56 This paper will refer to the woodlot, now called "Reynolds Woods", by its proper name--Herbst

Woods. Somewhere along the line, way back in 1863 accounts of the battle, writers began referring to the

woodlot or grove as McPherson's Woods. The grove's proximity to the McPherson farm buildings (ca. 500

feet) may have led to the association of one with the other. But the fact remains that the entire length and

width of the grove was owned by John Herbst at the time of the Battle of Gettysburg, and was the woodlot

portion of the 160-acre Herbst Farm. The McPherson woodlot, at that time, was north of the Cashtown Pike

and east of the James Wills Farm (in the area now erroneously called Sheads' Woods). The Herbst Woods

were never owned by Edward McPherson, John B. McPherson, or any other McPherson from the time

antecedent to the battle to the time after the battle.

To call the woods "McPherson Woods" now, after research which should have been checked routinely

decades ago, would be not only an untruth and a historical inaccuracy, but it is a disservice to John Herbst

himself. Everyone familiar with the battle knows about the McPherson barn, McPherson Woods, and

McPherson Ridge. As a matter of fact, the constant recurrence of the name McPherson leads one to believe

that his farm was the setting of the entire First Day's Fight. Such was not the case. Some of the severest

fighting took place on the Herbst Farm. Poor John Herbst had his barn burned because Yankee soldiers used

his buildings from which to snipe at Heth's men. (McPherson lost no buildings.) Archer's men and General J.

J. Archer himself (the first general officer to be captured since Lee took command in 1862) were captured on

the Herbst Farm. General Reynolds was killed in Herbst Woods. Our past histories of the battle should be

corrected so that a correct image of the battlefield itself can be projected. A trivial matter, perhaps, but why

has the Herbst Woods been called "McPherson Woods" for over one hundred years?

Because the fighting in Herbst Woods was important to the outcome of the struggle on the McPherson

Farm, we are including it in this study.

57 24 Michigan (496 present), 2nd Wisconsin (302 present), 6th Wisconsin (340 present), 7th

Wisconsin (370 present), and l9th Indiana (288 present). Total present for duty July 1, 1863, 1796 officers

and men. From Rufus R. Dawes, Service with the Sixth Wisconsin Volunteers (Marietta, Ohio, 1890;

William F. Fox, Regimental Losses in the American Civil War (Albany, 1889); ORs part 1; monumental

inscriptions.

58 Dawes, p. 164.

59 R. K. Beecham, Gettysburg: The Pivotal Battle of the Civil War (Chicago, 1911), p. 69.

60 Doubleday clung to these orders throughout the first day (even after Reynolds was killed and he

commanded the First Corps), forever having someone watching the Hagerstown Road. As he himself later

wrote: "The rebels, however, did not advance on the Fairfield road until late in the afternoon. They must

have been in force upon it some miles back, for the cavalry so reported, and this caused me during the entire

day to give more attention than was necessary to my left,... "

Abner Doubleday, Chancellorsville and Gettysburg, Campaigns of the Civil War series, vol. VI (New

York, 1882), p. 130.

61 Edwin B. Coddington, The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command (New York, 1968). p. 277.

Return to Text

62 OR, part 2, p. 646. Confederate and Union accounts differ as to the number who were captured with

Archer.

Return to Text

63 Beecham, pp. 66-67.

Return to Text

64 C. V. Tevis and D. R. Marquis, The History of the Fighting Fourteenth (Brooklyn, New York,

1901), p. 89. This painting purports to show the 14th Brooklyn in the cut, which is historically inaccurate. It

was Dawes's 6th Wisconsin which should have been painted here. Notice the McPherson barn in the right

background, showing the embrasures in the stone gable wall and siding of the forebay.

Return to Text

65 William H. Tipton photograph collection, #1802, GNMP library.

Return to Text

66 Lee himself said after the battle that it was all his fault--he thought his men were invincible.

67 Beecham, between pp. 88-89.

68 It is not quite certain what happened to the 55th North Carolina after they outflanked the 76th New

York and caused Cutler to fall back to Oak Ridge. They were not in the railroad cut during the surrender,

but it is a mystery as to their unrecorded whereabouts. Bachelder's maps put them clear back by Willoughby

Run. The llth Mississippi, the fourth regiment in Davis's Brigade, was on duty at Cashtown on July 1.

History of the One Hundred and Fiftieth Regiment Pennsylvania

Volunteers, Second Regiment, Bucktail Brigade

, (Philadelphia, 1905), p. 119.

72 Ibid., p. 122; J. H. Bassler "The Color Episode of the One Hundred and Forty-Ninth Regiment

Pennsylvania Volunteers," The Southern Historical Society Papers, vol. 37 (1909), p. 267.

73 Simon Hubler, "Just the Plain, Unvarnished Story of a Soldier In the Ranks: Exactly what a Corporal

in the 143rd Pennsylvania Infantry Did, Thought and Saw During the Three-Days' Battle," New York Times,

June 29, 1913.

74 Those unexpected shots from Oak Hill signaled the arrival of Ewell's Second Corps, especially

Rodes's Division.

75 Hubler.

76 Sergeant W. R. Ramsey to John Bachelder, April 16, 1883, Bachelder Papers, GNMP microfilm, reel

#3.

77 Bassler, SHSP, p. 268.

78 The color bearers and guards consisted of six men--Sergeant Brehm, Corporals F. W. Lehman, Fred

Hoffman, H. H. Spayd, John Fridell, and J. H. Hammell.

79 Bassler, SHSP, pp. 268, 274.

80 Ibid., p. 268.

81 Hubler.

82 OR, part 1. p. 249.

83 Major William Robbins, Journal, September 24, 1896, p. 31.

84 Ramsey to Bachelder.

85 OR, part 1, p. 249.

86 Chamberlin, p. 133.

87 John P. Nicholson, ed., Pennsylvania at Gettysburg, vol. II (Harrisburg, 1904), p. 751.

88 Ibid.

89 OR, part 1, p. 248.

90 Elias B. Weidensaul, killed in action, July 1, 1863.

9l Ramsey to Bachelder.

92 "The Colonel was of a noted New York family; drifted into lumbering at an early age in Tioga

County, Pennsylvania; and in the Spring of the year accompanied rafts down the Allegheny, Ohio, and

Mississippi rivers. Such a life inured him to hardships, but it was probably also through it that he acquired a

taste for strong drink, and on rare occasions he was liable to indulge beyond the point of safety. With this

exception he was the right

"man in the right place as Commander of a regiment; and it is a pleasure to mention, that though badly

wounded before leaving McPherson's, he stuck to the men until they reached town.

"It pains me to say ought against my old-time friend, but truth, historical accuracy, and justice to my

men, demand that the curtain be drawn aside and the Colonel's condition during the engagement on the

McPherson farm be revealed. . . . That Col. Dwight was drunk during the fight is well known to the men of

his regiment.

". . . . standing out distinct and prominent is the melancholy fact that it was the whiskey which muddled

his brain that is to blame for the loss of our flags.''

Bassler, SHSP, pp. 286, 288.

93 Ibid., p. 275.

94 H. H. Bassler to John Bachelder, September 5, 1881, p. 3.

95 Bassler, SHSP, pp. 282-283.

96 Chamberlin, pp. 129-130.

97 Hubler.

98 Beecham, p. 73.

99 Nicholson, p. 752.

100 Heth staked the site of his near-fatality thirty-one years after the battle when he visited and went over the field

with National Park Commissioner Robbins. The spot was a "short distance south of Meredith Avenue and about fifty

yards eastward from the 7th Wisconsin Monument". Robbins Journal August 18, 1894, p. 5.

A large white oak, just north of Herbst Woods and the old fence line, stands at fifty yards east of the 7th

Wisconsin monument. This tree, with a circumference of over nine feet now, is approximately 170 years old, and is

apparently the only old tree in this part of the field north of the woods. It would have been about one-third that size in

1863, but still impressive enough to have been remembered by Heth if he had been standing beside it observing the

advance when struck. (The tree would have been over four feet in circumference during Heth's 1894 visit to the

battlefield.)

This was one of three "color

incidents" on the McPherson Farm. To discourage the rapid retreat of the 150th Pennsylvania

from McPherson's Ridge, Colonel Huidekoper ordered Sergeant Samuel Peiffer and his color

guard to advance with the colors. While the regiment rallied and poured a volley into the

advancing Virginians, the color guard itself was riddled with bullets, and Peiffer himself fell

"bleeding from a mortal shot, while proudly flaunting the colors in the face of the foe". 96

Another color bearer, Benjamin Crippen, was immortalized in stone for his courageous bearing

during the retreat of the 143rd Pennsylvania across the McPherson Farm towards the seminary. Crippen

hung back from the rest of the regiment, stopping now and again to turn around, wave his flag, and shake his

fist defiantly at Brocken-

Another color bearer, Benjamin Crippen, was immortalized in stone for his courageous bearing

during the retreat of the 143rd Pennsylvania across the McPherson Farm towards the seminary. Crippen

hung back from the rest of the regiment, stopping now and again to turn around, wave his flag, and shake his

fist defiantly at Brocken-

65

brough's infantry. His act of defiance was Crippen's last service to his country and to the flag he so

vehemently protected. He was brought down by his angry pursuers, much to the regret of the onlooking

Confederate Lieutenant-General A. P. Hill. Crippen's regiment dashed back to save the colors, poured a

volley into the Virginians which momentarily staggered them, and then continued the retreat to the seminary.

Sgt. Ben Crippen & the 143rd Pennsylvania Monument

From Willoughby Run to Seminary Ridge the distance is not

great. It is 475 yards from the creek to the ridge at the eastern edge of the

[Herbst] woods, where our battle with Archer began in the morning; and

500 yards from the edge of the grove to the crest of Seminary Ridge. We

measured the ground carefully in

66

1900, because we remembered it as a good long two miles in that

day of battle. The whole distance is less than a thousand yards, but it

took Hill's Confederates five weary hours to travel it, and then they did

not quite reach the goal of their ambition until after we abandoned it from

other causes. 98

For these men who fought around the McPherson farm buildings on July 1, 1863 the stone barn

became a landmark, a defense, a refuge, a "fortress", a trap. It was briefly "fortified" by men of the 150th

Pennsylvania during the last desperate moments of their retreat from the McPherson buildings and quarry.

The barn, which had been a protection in the earlier part of the

engagement, as well as a convenient shelter for the wounded, now that

the enemy had forced their way up to it, became a veritable trap for our

own men. Those who were on the outside were started towards the town,

but a number had occupied the building, and were firing from every

opening looking towards their assailants. Besides these, there were many

wounded within, and a sprinkling of stragglers from various brigades and

regiments. 99

While many of the 149th and 150th escaped, a lot were "cut off at the barn or in passing the farm-house, by

the rapid closing in of the rebel lines on both sides" (from the north and west). Almost 200 were listed as

among the missing from the 149th and 150th alone.

Among the more famous casualties that fell on McPherson's land, besides those already mentioned,

was the eccentric civilian-soldier

67

John Burns, whose contribution and spirit were noted by Abner Doubleday in his official report of the battle

and in his history of the campaign. Three Yankee units claimed him as their own on July 1--Hall's 2nd

Maine Battery, the 150th Pennsylvania, and the Iron Brigade. Burns received three wounds that day and was

left on the field when the First Corps retreated. His resourcefulness and fortitude did not wane even when

suspected by Confederates of being a non-uniformed bushwhacker, and Burns escaped from a possible

hanging by crawling to his own home. Many have disparaged this local curmudgeon for bushwhacking,

getting lost, chasing cows, acting crazy, &c on that day, but he impressed those he fought beside (who must

have been satisfied to see at least one Gettysburg resident come out to help them in the defense of his

fireside). Indeed, he is one of only two recorded citizens to risk the noose and bullet in order to assist the

Federal forces. One wonders how much of the caustic remarks made by his neighbors about old John Burns

was inspired by guilt of those who hid in cellars or ran away, while the seventy-year old man risked life and

limb on the field of battle.

68

46 0R, part 1, p. 923.

Return to Text

Return to Text

Return to Text

Return to Text

Return to Text

Return to Text

Return to Text

Return to Text

Return to Text

Return to Text

Return to Text

Return to Text

Return to Text

Return to Text

Return to Text

Return to Text

Return to Text

Return to Text

69 Walter Clark, Histories of the Several Regiments and Battalions from North Carolina in the Great

War, 186l-65, excerpts (Raleigh, 1901), vol. II, pp. 341-360, passim.

Return to Text

70 Doubleday, p. 134.

Return to Text

71 Lt. Col. Thomas Chamberlin,

Return to Text

Return to Text

Return to Text

Return to Text

Return to Text

Return to Text

Return to Text

Return to Text

Return to Text

Return to Text

Return to Text

Return to Text

Return to Text

Return to Text

Return to Text

Return to Text

Return to Text

Return to Text

Return to Text

Return to Text

Return to Text

Return to Text

Return to Text

Return to Text

Return to Text

Return to Text

Return to Text

Return to Text