by

Eric J. Wittenberg

Eric J. Wittenberg is a Columbus, Ohio, attorney who is working on a full-length biography of John Buford. He was educated at Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pennsylvania, and the University of Pittsburgh School of Law. He is a prior contributor to this magazine, also on the topic of John Buford's contributions to the Gettysburg Campaign. This article had its genesis in a discussion which occurred in the Gettysburg Discussion Group, an Internet-based group of over 300 members who actively discuss the Battle of Gettysburg via e-mail. A number of members of the group gave the author assistance in the preparation of this article, and he is grateful for their help.

Jerome's account of the event was published in 1867 by John Watts DePeyster, along with a second manuscript that similarly promoted John Buford's role in the first day of the battle of Gettysburg in The Decisive Conflicts of the Late Civil War. 1 The second article may have been written by DePeyster himself, using the pseudonym of "Anchor." Jerome wrote his manuscript after an exchange of letters between himself and Maj. Gen. Win-field Scott Hancock, wherein Jerome implored Hancock to make certain that Buford's role in the battle would not be forgotten. Both Jerome and DePeyster clearly had an agenda in mind when they wrote their manuscripts, and this fact may very well have tainted their perceptions.

Lieutenant Jerome, often known as A. Brainard Jerome, was from New Jersey. He had enlisted in the 1st New Jersey Infantry in May 1861, was commissioned a second lieutenant in that regiment on August 31, 1861, and was promoted to first lieutenant in May 1863. On March 3, 1862, he was assigned to the newly created Signal Corps, in which he served during most of the early, major engagements of the Army of the Potomac.2 After the battle of Chancellorsville, Jerome was assigned as signal officer for Buford's cavalry division and thus had only served in this capacity for a few weeks by the beginning of the battle of Gettysburg.3 Perhaps Jerome did not have much opportunity to get to know Buford by July 1, 1863, but one thing is clear--Jerome greatly admired John Buford. This admiration led Jerome to take steps to preserve the memory of his hero.

Pursuant to Buford's orders, Jerome established a signal station in the cupola of the Lutheran Seminary on the morning of July 1, and provided intelligence to Buford as well as communications to the supporting corps. Jerome's manuscript published by DePeyster described Jerome's role on July 1, but a letter he wrote to General Hancock prior to penning the manuscript was also specific as to Jerome's involvement in Buford's stand against the advancing line of Lt. Gen. A. P. Hill's Confederates.4

Jerome spotted the Confederate advance, the approach of Maj. Gen. John F. Reynolds' First Corps, coming to Buford's aid, and later the advance of Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard's Eleventh Corps. According to both of Jerome's accounts, he was instrumental in interacting with Buford during the early part of the engagement. Jerome also recounted that he was sent by Buford to urge Howard forward to provide additional support.5 There was also a message to Howard that the compilers of the Official Records credited as being sent on July 2, and which was listed with a series of messages generated by a signal station on Little Round Top. This message, although undated by Jerome, was clearly sent on July 1, probably from the cupola of the Seminary, and complements the narrative of the manuscript and his letter to Hancock. Jerome signaled the approach of Lt. Gen. Richard Ewell's corps of the Army of Northern Virginia:

General Howard: Over a division of rebels is making a flank movement on our right; the line extends over a mile, and is advancing, skirmishing. There is nothing but cavalry to oppose them. A. B. Jerome First Lieutenant, Signal Officer6During the withdrawal of the Union forces on the afternoon of July 1, Jerome moved his signal station from the Seminary cupola to the steeple of the courthouse in Gettysburg.7

Buford also appreciated Jerome's talents and his contributions to the Union victory at Gettysburg. In his report of the battle, Buford wrote, "Lieutenant Jerome, signal corps, was ever on the alert, and through his intrepidity and fine glasses on more than one occasion kept me advised of the enemy's movements when no other means were available."8 When asked by Jerome to provide a letter outlining the utility of the signal corps to the cavalry as part of his preparations to justify a permanent organization for the corps, Buford wrote on November 20, 1863:

I have taken occasion to notice the practical working of the Signal Corps, U.S. Army, in the field, and regard it as a valuable auxiliary to an army. With the aid of their powerful glasses, acting as both scouts and observers, the officers who have acted with me have rendered invaluable service when no other means could have availed. I regard their permanent organization as a matter of first importance.9This letter is particularly significant, because it was written the day before Buford had to leave the Army of the Potomac due to a fatal illness. By the time this letter was written, Buford was already afflicted with the typhoid fever that would kill him three weeks later.10 That he found time to write such a letter while extremely ill indicates the high regard in which Buford held Jerome and the men of the Signal Corps.11 Following is Jerome's account of the events of the evening of June 30, 1863, and the morning of July 1:

It is obvious that Jerome greatly admired Buford; the general was a man worthy of such admiration. Buford's background provides insight into why Jerome thought so highly of the quiet Kentuckian.BUFORD IN THE BATTLE OF OAK RIDGE 12

The first day's fight at Gettysburg, A.M. Wednesday, 1st July, 1863 Buford marched into Gettysburg with his division on the afternoon of June 30th, and, passing through the town, [Col. William] Gamble's (First) Brigade encamped on the Cashtown road, while [Col. Thomas C.] Devin's (Second) Brigade encamped on the road to Mummasburg.13 Gamble scouted toward Chambersburg, while Devin scouted the country toward Carlisle as far as Hunterstown, capturing a number of Rebel stragglers, from whom important information was elicited. On the night of the 30th, General Buford spent some hours with Colonel Tom Devin (now Brevet Brigadier-General and Lieutenant-Colonel of the Eighth U.S. Cavalry), and, while commenting upon the information brought in by Devin's scouts, remarked that "the battle would be fought at that point," and that "he was afraid it would be commenced in the morning before the infantry would get up." These are his own words.

Devin did not believe in so early an advance of the enemy, and remarked that he would "take care of all that would attack his front during the ensuing twenty-four hours." Buford answered "No you won't. They will attack you in the morning and they will come 'booming'--skirmishers three deep. You will have to fight like the devil to hold your own until supports arrive. The enemy must know the importance of this position and will strain every nerve to secure it, and if we are able to hold it we will do well."

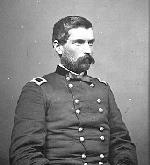

Miller, Photographic History, 1911

Maj. Gen. John F. ReynoldsUpon his return, he ordered me, then First Lieutenant and Signal Officer of his Division, to seek out the most prominent points and watch everything; to be careful to look out for camp-fires, and in the morning for dust.14 He seemed anxious, more so than I ever saw him. Early in the morning (1st July) I saw from the steeple of the Seminary a portion of their (Rebel) cavalry observing us from the Chambersburg pike.15 Upon reporting this, Buford prepared his small force, some 2,200 in all, for action, and very soon after the enemy moved up and opened with artillery, which was well replied to by our own light batteries.16 The engagement was desperate, as we were opposed to the whole front of Hill's corps. We held them in check fully two hours, and were nearly overpowered when, in looking about the country, I saw the corps-flag of General Reynolds (First Corps). I was still in the Seminary steeple, but being the only signal officer with the cavalry, had no one to communicate with, so I sent one of my men to Buford, who came up, and looking through my glass, confirmed my report, and remarked "Now I can hold the place."17 I am confident that he intended to retire to Cemetery Hill, and endeavor to hold on longer, but seeing Reynolds coming (some one and a half miles off) at the double-quick to his support, held on. General Reynolds and staff came up on a gallop in advance of their corps, when the following communication was made by me: "Reynolds, himself, will be here in five minutes, his corps is about a mile behind." Buford returned and watched anxiously my observations made through my signal-telescope. When Reynolds came up, seeing Buford in the cupola, he cried out: "What's the matter John?" "The devil's to pay," said he (Buford), and going down the ladder General R------ remarked that "he hoped Buford could hold out until his corps came up." With characteristic brevity Buford said: "I reckon I can." Reynolds then said "Let's ride out and see all about it," and, mounting, we rode out.18 The skirmishing was then very brisk, the cavalry fighting dismounted. General Buford told General R------ not to expose himself too much, but Reynolds laughed and moved nearer still. I think he must have been shot within twenty minutes from the time he arrived fairly upon the ground. The First Division of his corps moved up on a run, wheeled into line apparently without command, as solid as a stone wall, and were in action instantly, the cavalry holding the flanks. Shortly after this Buford's prophecy was fulfilled. "Booming, skirmishing three deep," came a line nearly a mile long, and it seemed that a handful of men could not hold them in check an instant. But taking advantage of every particle, fence, timber, or rise in the front, they held the whole force of Ewell's temporarily in check.19 One of my men (at the glass) came down to me with a message, saying that they saw infantry corps, and thought that it must be Howard's 11th Corps. This proved to be the case. Buford then ordered me to ride as fast as my horse could carry me and ask Howard to come up on the double-quick. I did so.20 Howard ordered his batteries forward, but his men came slowly straggling through the town, and got into action on the right. Their stay was of short duration. Buford from the signal station, then nearly surrounded, wrote in my dispatch book a communication to this effect. I can almost repeat the words: "For God's sake, send up Hancock. Everything at odds. Reynolds is killed, and we need a controlling spirit." This was either sent verbally to Meade or the dispatch is still in existence. I was the only signal officer at that time on the field, and consequently did not send it myself. Thus the poor general in his modesty laid down the laurels which should have crowned him the hero of the first day's fight. Hancock came up, took command, and this is what he tells me in a letter written in answer to one from me calling upon him to do justice to Buford's memory: 'In my report of the Battle of Gettysburg I did not fail to mention General Buford in fitting terms. I spoke of the handsome appearance of his cavalry when I arrived on the ground, as compared with other troops after I arrived on the ground. I regret that I did not know of his previous services on that day. Still it would not have been my province to recount it. I fear Buford will never have justice done for him for the first day's fight; still it shall not be my fault if he has not. I am not only glad to know that Buford, who was a good friend of mine always, spoke of me as you relate, but it has given me an opportunity, which I shall profit by, of bringing his deeds in more prominence in one of the histories about being published.'21

John Buford, Jr. was born near Versailles, Kentucky, on March 4, 1826. He was the first son of John and Anne Bannister Howe Watson Buford. Young Buford came from a large family--he had two full brothers, Thomas Jefferson and James Monroe, as well as thirteen half-brothers and sisters from the first marriages of both of his parents.22 His grandfather, Simeon Buford, had served in the Virginia cavalry during the Revolution under Col. Henry "Light Horse Harry" Lee, father of Gen. Robert E. Lee. Buford's grandfather also married a member of the Early family of Culpeper County, Virginia, making Buford and Confederate Maj. Gen. Jubal A. Early, of East Cemetery Hill fame, fourth cousins.

Buford's mother died of cholera in 1835, and the family relocated to Rock Island, Illinois. His father was an influential businessman and politician in the town, and the Buford family was among the first families of Rock Island.23 Young John Buford was "a splendid horseman, an unerring rifle shot and a person of wonderful nerve and composure."24 His dear friend Maj. Gen. John Gibbon wrote of Buford:

His boyhood was spent in close communion with the horse and he acquired an intimate knowledge of him, his nature and his powers, what he could do and what he could not do. He thus acquired in his boyhood the first essential of a good cavalryman in the knowledge of the character and capacity of the cavalryman's co-worker in the field. Buford was one of the best horsemen I ever saw. He delighted in the horse, was fond of riding, and it is said of him that 'as a boy he was the greatest dare-devil of a rider in the whole county.'25In 1841 Buford left Rock Island for Cincinnati, Ohio, where his older half-brother was working on an Army Corps of Engineers project on the Licking River. During this period, Buford attended Cincinnati College, now the University of Cincinnati, where "he acquitted himself well."26 Denied application to West Point in 1843 due to a War Department policy prohibiting two brothers from being appointed to West Point, John attended Knox Manual Labor College in Galesburg, Illinois, during the 1843-1844 academic year.27 His stay there was brief--after a brisk letter writing campaign by friends and family, Buford was appointed to West Point in 1844. His performance there was solid, if unspectacular. He graduated sixteenth in the class of 1848.28 Gibbon recalled:

Rather slow in speech, [Buford] was quick enough in thought and apt at repartee. He was not especially distinguished in his studies, but his course in the Academy was marked by a steady progress, the best evidence of character and determination.29Upon graduation, and at his own request, Buford was commissioned into the First Dragoons as a brevet second lieutenant. He remained with the First Dragoons for only a few months, and was transferred to the newly-formed Second Dragoons in 1849. He served as quartermaster of the Second Dragoons from 1855 through the beginning of August 1858, fighting in several Indian battles along the way, including the Sioux Punitive Expedition under command of Brig. Gen. William S. Harney, a campaign that culminated in the Battle of Ash Hollow in 1856. Ironically, the commander of a company of the Mounted Rifles that day was the young Lt. Henry Heth. Lt. Col. Philip St. George Cooke, father-in-law of J.E.B. Stuart and commanding officer of the Second Dragoons, cited Lieutenant Buford for his "good service" at Ash Hollow, as did Harney himself.

Buford participated in quelling the disturbances in Kansas during the mid-1850s, and served on the Mormon Expedition to Utah during 1857-58. He won high praise from Cooke during the arduous march west, and served in Utah until the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861.30 John Gibbon recalled:

One night after the arrival of the mail we were in his [Buford's] room, talking over the news . . . when Buford said in his slow and deliberate way, "I got a letter by the last mail from home with a message in it from the Governor of Kentucky. He sends me word to come to Kentucky at once and I shall have anything I want." With a good deal of anxiety, I asked, "What did you answer, John?" and my relief was great when he replied, "I sent him word I was a captain in the United States Army and I intend to remain one."31Reporting to Washington with his regiment, Buford requested and was assigned as a major in the inspector general's office. He served there until June 1862 when his old friend from the Regular Army, Maj. Gen. John Pope, now commanding the Army of Virginia, helped Buford get promoted to brigadier general of volunteers, and gave him command of a brigade of cavalry.32 Buford served with distinction during the Second Manassas Campaign, providing superior scouting and intelligence services, and also going toe-to-toe with the vaunted troopers of Stuart's cavalry. Buford's men nearly captured both Stuart and Robert E. Lee at different points during the campaign, and Buford's intelligence saved Pope's army from destruction shortly after the August 9, 1862, battle of Cedar Mountain. Buford commanded the Union forces in a little-known but important phase of the battle of Second Manassas, the cavalry fight at Lewis Ford on August 30, 1862, where Buford enjoyed some success against Stuart's men and bought time for the beaten Army of Virginia's retreat. Buford himself was slightly wounded in this engagement.33

As a result of his wound, Buford was appointed chief of cavalry of the Army of the Potomac under George McClellan on September 9, 1862, and served in this purely administrative capacity until February 1863, when, at his own request, Buford was appointed to command the Regular cavalry of the Army of the Potomac's newly-formed cavalry corps. Buford, with no field command, was with the Army of the Potomac's headquarters at the battle of Antietam on September 17, 1862, and was present when Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker was wounded. Buford heard Hooker state that it was his wish that Maj. Gen. George G. Meade be given command of his corps in his absence. Buford rode back to army headquarters and so informed McClellan, who issued the necessary orders. Buford, foreshadowing the efforts described by Jerome, had the foresight to get the right commander to the right place on a battlefield, much as he did for Hancock on July 1, 1863.34

In command of the Reserve Brigade, Buford performed capably during the April-May 1863 Stoneman Raid on Richmond, and did extremely well in command of the right wing of the Cavalry Corps during the Battle of Brandy Station on June 9, 1863. His troopers bore the brunt of a fourteen-hour fight that day, and one of his brigade commanders was killed during the opening phases of the battle. Buford was appointed to command the First Division of the Cavalry Corps immediately after the battle of Brandy Station and held that post on July 1, 1863.

His men were a credit at the battle of Upperville, Virginia, on June 21, 1863, where his division bested two brigades of Confederate cavalry and horse artillery in a day-long fight. Immediately after the Battle of Upperville, elements of Buford's command spotted the sprawling camps of one of the brigades of Lt. Gen. James Longstreet's corps in the Shenandoah Valley. This provided the high command of the Army of the Potomac with concrete intelligence about the location and movements of the Confederate infantry.35

By June 29, 1863, Buford suspected that a battle would soon rage in south-central Pennsylvania. Standing at the opening of Monterey Pass through South Mountain and overlooking the plains and rolling countryside that makes up the Cumberland Valley of Pennsylvania, Buford said, to nobody in particular, "Within forty-eight hours, the concentration of both armies will take place on some field within view, and a great battle will be fought."36 John Buford's prophecy proved correct.

In July 1863 John Buford was thirty-seven years old and was one of the best cavalrymen in either army. He was a man of few words, yet full of energy. Col. Charles S. Wainwright, chief of artillery of the First Corps, wrote that Buford was "never looking after his own comfort, untiring on the march and in the supervision of his command, quiet and unassuming in his manners."37 Lt. Col. Theodore Lyman, of General Meade's staff, met Buford in the fall of 1863 and wrote the following description:

He is one of the best officers of [the Union cavalry] and is a singular-looking party a compactly built man of middle height with a tawny mustache and a little triangular gray eye, whose expression is determined, not to say sinister. His ancient corduroys are tucked into a pair of ordinary cowhide boots and his blue blouse is ornamented with holes; from one pocket thereof peeps a huge pipe, while the other is fat with a tobacco pouch. Notwithstanding this get-up, he is a very soldierly looking man. He is of a good natured disposition, but not to be trifled with. Caught a notorious spy last winter and hung him to the next tree, with this inscription: "This man is to hang three days; he who cuts him down before shall hang the remaining time."38General Gibbon, a good soldier in his own right, called Buford "the best cavalryman I ever saw." Perhaps most telling, Buford was known to his comrades as "Old Steadfast."39 By the time of the battle of Gettysburg, the hardships of many years of service had taken their toll on Buford. During the campaign, "he suffered terribly from rheumatism, and for days could not mount a horse without help, but once mounted, he would remain in the saddle all day."40 In battle, Buford was a fearless front-line commander. On one occasion, he "dismounted and walked up a hill to see how the day was going, when a bullet passed through his blouse, cutting five holes."41 On another:

. . . an officer rode up to General Buford saying that some rebel batteries were posted on the opposite side of the river having range of the road, and we had better move some other way. He had not finished speaking, however, when a shell hit a tree, not a rod from him, and, glancing, struck the ground in our midst, the fuse burning and hissing. As if by instinct the General and his staff spurred their horses, and barely escaped as, the next moment the shell exploded. . . .42Blessed with great talent and fine subordinates to carry out Buford's wishes, it is no wonder that Jerome admired Buford so much. Others did as well. One admirer wrote a series of anonymous pieces in the post-war Army-Navy Journal. Rather than identify himself, this author simply signed his work with the pen name "Anchor." These articles were then gathered and published as a set by Bvt. Maj. Gen. John Watts DePeyster of New York.43

Writing under pseudonyms was not an uncommon practice during the Civil War-era. For example, while it is not known for certain, the series of vitriolic articles that appeared under the pen name "Historicus" are generally deemed to have been written by Maj. Gen. Daniel E. Sickles, in an attempt to defend his actions at the battle of Gettysburg. The Historicus pieces spurred a series of responses by another anonymous author who called himself "Truth," someone rumored to have been General Gibbon. Writing anonymously protected careers and shielded the author from direct attack.

It is possible that "Anchor" may have been DePeyster himself. There are a number of reasons for this conclusion. First, a close look at the "Anchor" manuscripts reveals that their author possessed a detailed knowledge of military history. Second, the articles favorably assess Maj. Gen. Daniel E. Sickles' role and his contributions to Union victory in the battle of Gettysburg. Finally, nearly all of the "Anchor" pieces were written in Tivoli, New York, DePeyster's hometown.

Who was DePeyster? John Watts DePeyster was born on March 9, 1821, the son of a wealthy and powerful New York family. He was a first cousin of Civil War hero Maj. Gen. Philip Kearny, the one-armed, swashbuckling general killed at Chantilly on September 1, 1862. He was also a nephew of the legendary dragoon, Brig. Gen. Stephen Watts Kearny. DePeyster inherited vast wealth at a young age, more than one million dollars by the time he was twenty-one. He was educated at Columbia College, today Columbia University, but never graduated due to poor health. In 1845 he entered state service in New York and was soon named colonel of a militia regiment. The consistently poor state of his health prohibited him from commanding troops in the field. Despite this fact, he held the rank of brigadier general in the New York State Militia and was named inspector general. He continued to serve in an administrative capacity throughout the war. He nevertheless achieved the rank of brevet major general of the New York State Militia in 1866.

DePeyster and his family resided on an estate--Rose Hill--located in Tivoli, Duchess County, New York. He was a prolific writer and an accomplished military historian. After the Civil War, he was known as "America's foremost military critic." In that capacity, he published hundreds of pieces, including, perhaps, approximately fifty under the pseudonym "Anchor."44 One commentator noted DePeyster's "keen eye for topography, his long and still unceasing military education, his uncommon memory, his power of description and his opportunitites for using his abilities constitute him the only as well as the first military critic in America."45 DePeyster "rejoiced in overriding conventionalities and often showed strong bias, particularly in defense of a familial connection, but his writings show exceptional knowledge of military history and science."46 This kind of erudition comes through plainly in the "Anchor" manuscripts.

DePeyster was a close friend and confidant of General Sickles, and was actively involved in "alumni" activity of the Third Corps. An organization called the Third Army Corps Union was formed as a beneficial society for the wives and children of veterans of the Third Corps, and DePeyster helped write its history.47 Long his cousin's advocate, DePeyster also wrote a fawning biography of Kearny.48 For some reason there were a few portions of The Decisive Conflicts of the Late Civil War where the "Anchor" pseudonym was used, as in the following:

Even though DePeyster was not physically present at Gettysburg, he nevertheless had an extensive knowledge of Buford's activities there. The above analysis, possibly written by DePeyster, clearly supports Jerome's version of the story of Buford's role in the first day's battle at Gettysburg.JOHN BUFORD AT GETTYSBURG Wednesday, July 1st, 1863.

The first collision on free soil

"My man's as true as steel."

"Boot, boot into the stirrup, lads, and hands once more on rein;

Up, up into the saddle, lads, a-field we ride again:

Off, off we ride, in reckless pride, as gallant troopers may

Who have old scores to settle, and long slashing swords to pay.

The trumpet calls 'Trot out! Trot out!'--we cheer the stirring sound;

Swords forth, my lads! through smoke and dust we thunder o'er the ground.

Good luck befall each trooper tall, that cleaves to saddle-tree,

Whose long sword on Rebel sconce the rights of Majesty." Few persons can comprehend the extent to which the movements of the Loyal and Rebel armies were involved prior to Gettysburg. Lee advanced up the Cumberland valley, reaching Chambersburg, in force, June 27th, west of the South Mountain; Hooker, afterward Meade, through the lowlands east of the Catoctin Mountains, which die out near Emmitsburg. The Union army entered into Maryland and moved toward Frederick City June 25th. Lee excuses himself for his ignorance of the movements of the Union forces on the plea of the absence of Stuart with his cavalry. These latter actually crossed the Potomac at Seneca Creek, June 27th, so far to the east that the Loyal army for a time was interposed between them and the main Rebel forces. Meanwhile Buford, charged with the duty of covering the left of the Union army, crossed the Potomac near Shepherdstown, followed up the same valley as the Rebels, west of the mountains, between Lee and Meade as it were, but entirely independent of the latter.49 He marched through Middleton, struck the Rebel trail, and re-crossed the South Mountain by the Monterey Pass, and was on the flank and almost in the rear of a body of Rebels below him in the Carrol Tract. This was part of [Brig. Gen. J. Johnston] Pettigrew's Brigade of Heth's division of Hill's corps, which had crossed the South Mountain from Chambersburg to Cashtown, and thence had pushed off southward, at right angles, reaching Fairfield or Millerstown, on the road from Hagerstown to Gettysburg, June 29th. The same night Buford was in bivouac at Fountain Dale, where the road from Hagerstown bifurcates, the left branch leading to Gettysburg, the right to Emmitsburg, whither he had orders to proceed. Seeing the Rebel camp-fires in the valley below, Buford got his men in the saddle early A.M., June 30th and surprised the Rebel detachment at Millerstown or Fairfield, which fell back precipitately along the road by which it had advanced.50 The language my informant (Hon. J. McC--------) used was, "They mutually recoiled from each other." The Rebels thus unexpectedly hit by Buford were not more surprised by his appearance from the direction of their own army than was Buford at finding a hostile force within a few miles of the spot where he expected to meet our own troops. Buford, who was one of those rare soldiers who believe in the literal obedience of orders, and yet exercise common-sense, did not follow up the Rebels, but counter-marched to Fountain Dale, and thence continued on to Emmitsburg as directed, arguing that if he followed them up when they recoiled from his blow such a course might militate against the general plan of operations. When he arrived at Emmitsburg and found that he was free to act, he then evinced as much soldierly instinct as he had previously shown implicit obedience. He at once, in obedience to the orders of his superior, the prescient [Alfred] Pleasonton, retraced his steps, as it were, to Gettysburg, entering the town as two of Hill's brigades were actually about to occupy Seminary Ridge.51 Finding Buford in the place they fell back to Marsh Creek, and hid themselves in the woods along that stream, whose name is a misnomer, since its waters are pure and clear. It is highly probable that the Rebels had previously learned through a "sympathizing" friend, that Buford was near at hand, since they attempted to set a trap for him there. One Rebel regiment defiled under cover of the hills to the right of the road, another to the left, while a third was thrown forward a short distance toward Gettysburg, to try and induce our cavalry to pursue, or rather adventure an attack. In this position the Rebels remained for about two hours, when they fell back toward the mountains and went into camp.52Night fell and the moon rose, and by its light the Rebels were hurrying up from the west and north and east; the Union forces from the east and south.

It is not generally known, in fact the contrary has often been asserted, that the battle at Gettysburg was fought

"Where mountains rise, umbrageous dales descend,"

in the light of a full moon, which, if any of our "Boys" plodding thitherward to rescue their northern homes, ever read [Alexander] Pope, must have recalled his beautiful lines, so appropriate to the scene and the hour:

"As when the moon, refulgent lamp of night,

O'er heaven's pure azure spreads her sacred light,

O'er the dark trees a yellower verdure shed,

And tipp'd with silver mountain head;

Then shine the vales, the rocks in prospect rise;

The 'march-worn troops,' rejoicing in the sight,

Eye the blue vault and bless the useful light."However cloudy, it could not have been absolutely dark at any time on the nights of the 1st to the 6th of July, 1863. The moon was at its full July 2nd, and rose at 8h.38m. p.m.

Buford encamped his command beyond the town, feeling toward Cashtown, at the same time that the Rebels were simultaneously feeling toward Gettysburg.53 Finding that Buford had only cavalry, the Rebels then advanced determinedly in force. The news of this movement was reported to Buford very early July 1st. Thereupon, he pushed forward his picket line to Willoughby's Run, and developed his line of battle on the lower ridge, westerly between that Run and Seminary or Oak Ridge. Then and there the battle proper, preliminary to that of Gettysburg commenced. Had it not been for these fortuitous circumstances, the Rebels would have occupied the strong positions which they afterward endeavored in vain to make themselves masters of. Thus is due to Buford's prompt and bold execution of Pleasonton's directions, and in action to him alone, the successful initiation of the maneuvers which insured the occupation of that natural stronghold which proved impregnable to the best army which the Rebels ever possessed. Consequently it is no more than justice to claim that the North owes to the soldierly instincts, energy, and tenacity of John Buford the possession of the position of Gettysburg, and the fortunate issue of that decisive conflict. "To the intrepidity, courage, and fidelity of General Buford," says General Pleasonton, "and his brave division, the country and the army owe the battle-field of Gettysburg. His unequal fight of four thousand men against eight times their numbers, and his saving the field, made Buford the true hero of that battle."54 Although he is dead, let us hand this chaplet of honor upon the tombstone of one of the finest cavalry officers developed by the war. He and Reynolds were the heroes of the first day's fight, which has been very erroneously entitled the Battle of Willoughby's Run. Its far more appropriate name would be BATTLE OF OAK RIDGE, since there it was that Buford made his determined stand; there it was Reynolds died for his country; and there it is that the latter's memorial stone should stand in commemoration of his gallantry and untimely fall.

In some respects this battle of Oak Ridge resembles the battle of Quatre Bras, June 16, 1815, since both were fought to secure a position, which makes the parallel between Gettysburg and Waterloo still more remarkable.

ANCHOR

Jerome may very well have shared his observations of Buford with DePeyster and probably also shared concerns about preserving the memory of Buford's contributions. If so, it was not the first time that Jerome approached an influential patron for assistance in accomplishing his goals. Although Jerome resigned his commission in the Signal Corps in September 1864, he rejoined the army as a second lieutenant in the 8th Cavalry in June 1867, around the time that The Decisive Conflicts of the Late Civil War was published. 55Prior to writing his Buford manuscript, Jerome wrote the following letter to General Hancock:

A few moments after the death of Major General Reynolds, the late General Buford wrote a short despatch [sic] in my notebook to Major General Meade. If that message can be found it would add still greater lustre to your well won reputation. The purport of that dispatch was this; "For God's sake send up Hancock, everything is going at odds and we need a controlling spirit." Yet General, in all the parade that has taken place since of names and incidents, memories oratorical and poetical from Edward Everett to General Howard, have you not noticed that your friend the heroic Buford has been nearly disregarded? I was a young Lieutenant and Staff officer, and loved the General, and I am sure you will pardon me if I call your attention to this injustice.This letter was answered by Hancock, and is referred to in the closing paragraph of Jerome's manuscript. The similarities between the letter and the manuscript are striking, but there are differences. Jerome did not mention the "the devil's to pay" comment, and he failed to indicate that he left with Buford to ride to McPherson's Ridge with Reynolds. However, the detailed description of Buford in the cupola is extremely similar. There are some lines in both the letter to Hancock and the manuscript that tend to aggrandize Jerome's role. The letter recounted: "I reported their advance" and "I called the attention of the General, to an Army Corps advancing some two miles distant. . . ." The manuscript is slightly more hyperbolic: "I sent one of my men to Buford, who came up, and looking through my glass, confirmed my report, and remarked 'Now I can hold the place.'" The clear intention of both pieces is to glorify Buford.A squadron of the "1st Cavalry Division" entered Gettysburg driving the few pickets of the enemy before them. The General and staff took quarters in a hotel near the Seminary. As signal officer, I was sent back to lookout for a prominent position and watch the movements of the enemy. As early as seven A.M. I reported their advance, and took my station on the steeple of the "Theological Seminary." General Buford came up and looked at them through my glass, and then formed his small Cavalry force. The enemy pressed us in overwhelming numbers, and we would have be[en] obliged to retreat but looking in the direction of Emmitsburg I called the attention of the General, to an Army Corps advancing some two miles distant, and shortly, distinguished it as the First on account of their "Corps Flag." The Gen. held on with as stubborn a front as ever faced an enemy, for half an hour, unaided, against a whole corps of the rebels, when Gen. Reynolds and a few of his staff rode up on a gallop and hailed the General who was with me in the steeple, our lines being but shortly advanced. In a familiar manner Gen. Reynolds asked Buford "how things were going on," and received the characteristic answer "let's go and see." In less than thirty minutes Reynolds was dead, his corps engaged against fearful odds, and Howard only in sight from my station, while the enemy were advancing on the right flank in numbers as large as our whole front. It was then the despatch before alluded to was written. I carried a verbal message to Gen. Hancock asking him to "double-quick" for life or death. When evening came the enemy had possession of the town, but many of the "First Division" rode round rather than retreat through it. Excuse me, Gen., but it will be difficult to find a parallel in history to the resistance made by a small force of Cavalry against such odds of Infantrymen. This letter has been suggested by a paragraph in the New York papers, stating that you had just returned from Gettysburg and giving an account of your remarks etc. etc. Will you not General, endeavor to bring General Buford's name more prominently forward?

Everyone knows that he "in his day" was first and foremost. I have the honor to enclose an extract from his report which will show, I presume, that I speak from actual experience.56

One of the issues addressed by Jerome is where the initial meeting between Buford and Reynolds occurred, and over the years a controversy has developed over where that meeting actually did take place. Jerome adamantly stated that the first encounter between Reynolds and Buford took place at the Seminary, with Buford in the cupola. Jerome was specific in detail and laid out the reason for Buford being there during that portion of the fight. His explanations for Buford's presence in the cupola were logical and well-reasoned.

Library of Congress

Library of CongressWhen I reached the pike, there galloped past me a general and his staff, who upon reaching the top of the ridge, turned into the lane toward the Seminary building. This I have always believed was General Reynolds coming onto the field and going to the Seminary where he had an interview with General Buford (then on the cupola of the Seminary), before going out where the battle was then in progress. The time was about 9 o'clock or near it, and our infantry had not come up yet.57Skelly's account is suspect in that it was written nearly sixty years after the battle and well after the legend of the Seminary meeting was established. Young Skelly claimed to have been at too many key places on the first day for his account to be considered credible. He probably did not know who was in the cupola. However, it is possible that he saw Reynolds ride toward the Seminary building. Whatever the case, this account is one of the few existing primary sources to corroborate Jerome's account of the meeting between Buford and Reynolds. Even though it cannot be given too much credence, it is still a part of the story and as such merits examination.

A conflict arises between Jerome's account and Gibbon's recollection that by the time of the battle of Gettysburg, Buford was so afflicted with rheumatism that he often had to remain in the saddle all day, since getting on and off of his horse was too difficult. Assuming for a moment that Gibbon was correct, Buford's many trips up and down the steps to the cupola would have been excruciating for him. Gibbon's recollection regarding the status of Buford's health is in direct conflict with the portrait of the vigorous and dynamic Buford portrayed by Jerome.

In addition, there are other conflicting versions of the first meeting between the two leaders. Sgt. Charles H. Veil, Reynolds's orderly, wrote to David McConaughy in April 1864 in response to inquiries McConaughy made as part of his preparations to preserve the battlefield. In his letter, Veil wrote, "When we got into town we saw that there was considerable excitement, so the Genl [Reynolds] rode to the front at once--found Genl Buford engaged on ridge in front of Seminary supporting his batteries just in advance of it."58 Edwin B. Coddington concluded that Reynolds found Buford at his main line of resistance on McPherson's Ridge and discounted Jerome's version primarily as a result of Veil's account and thought that it would have been "more logical, when the situation was getting tight, for Buford to have been at the front than a half mile to the rear."59

Other historians have used the Veil account to discount the Jerome version. Dr. Richard Sauers wrote that the Jerome account was "probably untrue," and based his conclusion on both the Veil account and the question of whether Buford would have been in the cupola and not on McPherson's Ridge with his troopers as they held off the Confederate approach.60

Veil clearly did not mention any meeting at the Seminary. Further, his account was ambiguous in its identification of Buford himself or his force. Veil was with Reynolds when he fell, so presumably he was also with Reynolds when the meeting with Buford occurred. Veil, however, referred to spectators being in the cupola of the Seminary, speaking of Reynolds' advance with "enthusiastic admiration." If Veil was with Buford and Reynolds on McPherson's Ridge, it would have been extremely difficult for him to have heard such comments being made. This reference adds to the ambiguity of the account. Further, Veil was a young enlisted man, and it is simply unlikely that he would have been in earshot of high-level discussions by ranking officers such as Reynolds and Buford. Therefore, the reliance on the Veil piece as evidence that the meeting between Reynolds and Buford occurred on the front lines near McPherson's Ridge is probably misguided.

Another interesting account was written by Gettysburg citizen Henry E. Jacobs, who recalled years later, "About ten o'clock word came that the First Corps was approaching. I was fortunate enough to be opposite the Eagle Hotel when General Reynolds and Buford dismounted and, after a brief rest, rode out the Chambersburg Road. They made their way to the seminary cupola."61 If this account is accepted, Buford and Reynolds met in the town, rested a moment, and then rode out to the firing lines, with an initial stop at the cupola. This is also an unlikely scenario. Buford's men were hotly engaged and in danger of being flanked when Reynolds arrived. Given Buford's level of anxiety about the situation, it is doubtful that he would have left his command and ridden into town. Also, this account was written fifty years after the battle, and must be discounted when compared to more contemporary accounts.

Yet another account was written by Reynolds's aide-de-camp, Capt. Stephen Minot Weld. Weld was with Reynolds when Reynolds rode into the town and apparently witnessed the meeting between the two leaders. Weld was a good officer. Commissioned a second lieutenant in the 18th Massachusetts Infantry in January 1863, he was rapidly promoted for good service and was a captain at Gettysburg. In January 1864, he was reassigned as lieutenant colonel of the 56th Massachusetts and was promoted to colonel on May 31, 1864. Weld was brevetted brigadier general of volunteers on March 13, 1865, for gallant and meritorious service throughout the Civil War and was mustered out on July 12, 1865.62Weld was a close friend of Capt. Craig Wadsworth of Buford's staff, spent a lot of time with Buford and his staff officers, and evidently knew Buford well. Weld, a man of integrity and respect, idolized Reynolds as much as Jerome idolized Buford.

On July 1, 1863, Weld wrote in his diary, "When we reached the outskirts of Gettysburg, a man told us that the rebels were driving in our cavalry pickets, and immediately General Reynolds went into the town on a fast gallop, through it, and a mile out on the other side, where he found General Buford and the cavalry engaging the enemy, who were advancing in strong force." Later, Weld wrote an additional entry to clarify some of the ambiguity of this account:

. . . we rode out and saw the Confederates' batteries going into position on Seminary Hill, the lines of battle forming and skirmishers being thrown out. Opposed to them were our cavalry skirmishers, spread out like the fingers of the hand, falling back and firing, and, as I remember it, occasionally firing from a field battery. After seeing this, General Reynolds rode back to the town, went into a field on the right of the road and talked two or three minutes with General Buford, and then called his staff all around him. . . .63There are problems with this account as well. For one, Weld mistook McPherson's Ridge for Seminary Ridge, calling it "Seminary Hill," bringing the reliability of the account into question. Nevertheless, this account corroborates that of Jacobs, in that Weld has Reynolds meeting Buford somewhere other than on Seminary Ridge.

Maj. Joseph G. Rosengarten, another of Reynolds' staff officers, left a detailed account of Reynolds' death, but did nothing to clarify the issue of where the meeting occurred. Rosengarten wrote:

When he got Buford's demand for infantry support on the morning of the first, it was just what Reynolds expected, and with characteristic energy, he went forward, saw Buford, accepted at once the responsibility, and returning to find the leading division of the First Corps ([Brig. Gen. James S.] Wadsworth's), took it in hand, brought it to the front, put it in position, renewed his orders for the rest of the corps, assigned the positions for the other divisions, sent for his other corps, urged their coming with the greatest speed, directed the point to be held by the reserve, renewed his report to Meade that Buford had found the place for a battle, and that he had begun it, then calmly and cooly hurried some fresh troops forward to fill a gap in his lengthening lines, and as he returned to find fresh divisions, fell at the first onset.64Although Rosengarten was obviously present at the time that Reynolds was shot, his account did nothing to clarify the question of where the meeting between Buford and Reynolds occurred.

"Anchor," presumably DePeyster, added another facet to the debate in a piece titled "The Death of Reynolds," which also appeared in The Decisive Conflicts of the Late Civil War. In that piece, "Anchor" stated, "Reynolds, finding the excitement very great in the town, rode out at once to Buford, who had established his first line on the western slope of the cultivated swell, from half to three-quarters of a mile in front or west of Seminary Ridge, supporting his batteries just in advance of it."65This account indicated the position of Buford's line but failed to mention the Seminary meeting. This may reflect the fact that "Anchor" was not at the battle of Gettysburg and had no personal knowledge of the events that occurred there.

While the truth may never be known, the Jerome version, with its extensive detail, leaves the least room for doubt. Despite its conflict with Gibbon's account of Buford's physical condition, Jerome's account seems too detailed for it to have been entirely false. Moreover, Jerome was consistent in his recounting of the story. The other accounts are ambiguous in that it is unclear whether they refer to Buford's force or to the general himself. The first meeting between the two Union commanders most likely took place at the Seminary, as related by Jerome.

Another relevant issue is what role Buford played in bringing General Hancock to the Gettysburg battlefield. Jerome claimed that Buford sent a dispatch specifically requesting that Hancock be sent to the front. As there is no surviving record of such a dispatch, it is unclear whether it was sent. What is clear is that Buford sent a dispatch to his corps commander, Brig. Gen. Alfred Pleasonton, about 10:15 on the morning of July 1: "A tremendous battle has been raging since 9:30 a.m., with varying success. At the present moment, the battle is raging on the road to Cashtown, and within short cannon range of [Gettysburg]. General Reynolds was killed early this morning. In my opinion, there is no directing person."66It is unclear whether this is the dispatch that Jerome referred to in his narrative. It is clear, however, that Hancock was sent to the battlefield by Meade in response to the crisis. Something caused the commanding general to do so.

Regardless of whether Jerome embellished the truth, the fact is that Buford had the foresight to call for help when he needed it, when the fate of the army hung in the balance. He was, as at Antietam, in the right place at the right time, and his foresight led directly to the placement of the proper hand on the engine of command. Such is the hallmark of an outstanding combat commander.

Jerome and DePeyster did much to bring the actions of Buford to the public's attention. By allowing Jerome to publish his manuscript in the book, DePeyster did much to preserve the memory of Buford. Further, DePeyster vigorously campaigned for Buford himself and chose to pay tribute to him in the book. Had they not advocated so vigorously for Buford, his contributions to the great Union victory at Gettysburg may have been forgotten over the passage of time. Thus, Jerome and DePeyster are in no small way responsible for the preservation of the memory of the man who selected the battlefield at Gettysburg.